-

Caro Visitante, por que não gastar alguns segundos e criar uma Conta no Fórum Valinor? Desta forma, além de não ver este aviso novamente, poderá participar de nossa comunidade, inserir suas opiniões e sugestões, fazendo parte deste que é um maiores Fóruns de Discussão do Brasil! Aproveite e cadastre-se já!

Você está usando um navegador desatualizado. Ele poderá não mostrar corretamente este fórum.

Você deve atualizá-lo ou utilizar um navegador alternativo.

Você deve atualizá-lo ou utilizar um navegador alternativo.

Clube de Leitura 1º conto - O chamado de Cthulhu (H.P. Lovecraft)

- Criador do tópico Melian

- Data de Criação

Siker

Artista Comercial / Projetista Gráfico

Já que é conto, e bem curto, então vamos poder comentar logo sobre tudo né? A história é dividida em 3 partes, mas é tudo tão curto.Todo mundo fez igual eu e não leu o conto ainda, só que ao contrário, né?

E estou esperando alguém começar a comentar para depois falar algo.

Jeff Donizetti

Quid est veritas?

Acho que ninguém (eu inclusive) quer ser o primeiro a comentar sobre o primeiro conto do clube...  Será que é medo?!

Será que é medo?!

Falando em medo, podíamos começar discutindo se a leitura de O Chamado de Cthulhu despertou isso em nós. Vou citar palavras do próprio Lovecraft sobre o assunto como ponto de partida:

Será que é medo?!

Será que é medo?! Falando em medo, podíamos começar discutindo se a leitura de O Chamado de Cthulhu despertou isso em nós. Vou citar palavras do próprio Lovecraft sobre o assunto como ponto de partida:

"A emoção mais forte e mais antiga do homem é o medo, e a espécie mais forte e mais antiga de medo é o medo do desconhecido. Poucos psicólogos contestarão esses fatos, e a sua verdade admitida deve firmar para sempre a autenticidade e a dignidade das narrações fantásticas de horror como forma literária.

(...) O mais importante de tudo [numa narrativa de horror] é a atmosfera, pois o critério final de autenticidade não é o recorte de uma trama e sim a criação de uma determinada sensação. (...) O único teste verdadeiro para o horror é simplesmente este: se suscita ou não no leitor um sentimento de profunda apreensão, e de contato com esferas diferentes e forças desconhecidas; uma atitude sutil de escuta ofegante, como à espera do ruflar de asas negras ou do roçar de entidades e formas nebulosas nos confins extremos do universo conhecido. E, é claro, quanto mais complexa e unificadamente uma história comunique uma tal atmosfera, tanto melhor é como obra de arte no gênero considerado."

Fonte: LOVECRAFT, H.P. O Horror Sobrenatural na Literatura. (trad. João Guilherme Linke). Rio de Janeiro: Francisco Alves, 1987. pp. 1 e 5-6.

Última edição:

Siker

Artista Comercial / Projetista Gráfico

Eu não consegui notar nada que pudesse dar medo, em todas as adaptações (filme e jogo) é possível sentir o clima sombrio que aterroriza e assusta, toda a mitologia por trás de Cthulhu traz um certo horror, porém no conto eu não consegui sentir o terror; o medo do desconhecido, no conto, é algo que instiga mais do que assusta, ao meu ver a escrita do Lovecraft focou mais em manter um suspense interessante do que em causar pesadelos.Falando em medo, podíamos começar discutindo se a leitura de O Chamado de Cthulhu despertou isso em nós.

Pelo menos em mim ele não conseguiu suscitar este sentimento de profunda apreensão.

Tilion

Administrador

O principal do conto não é o medo que ele pode causar no leitor, mas sim a criação da atmosfera na qual está envolta a história, e é nela que está o terror; e os personagens, por estarem dentro dessa atmosfera e a vivenciando em primeira (ou segunda, no caso do narrador) mão, são os principais afetados por ela, com consequências desastrosas, físicas e mentais. (Tema recorrente nos contos do Lovecraft: conhecimento demais sobre o que devia ser deixado quieto = perdição).

Vikingaälva

Samson came to my bed

Alguém sabe me dizer quais diferenças principais entre o H. P. Lovecraft e o Poe?

Beren

Wannabe Rider

O principal do conto não o medo que ele pode causar no leitor, mas sim a criação da atmosfera na qual está envolta a história, e é nela que está o terror; e os personagens, por estarem dentro dessa atmosfera e a vivenciando em primeira (ou segunda, no caso do narrador) mão, são os principais afetados por ela, com consequências desastrosas, físicas e mentais. (Tema recorrente nos contos do Lovecraft: conhecimento demais sobre o que devia ser deixado quieto = perdição).

Exatamente o que eu penso ao ler Lovecraft.. a primeira coisa que li foi "O Caso de Charles Dexter Ward" e confesso que fiquei impressionado e com medo, mas recentemente comecei a ler os primeiros contos publicados pelo Lovecraft e não tinha o mesmo peso, mas quando me coloquei na posição do narrador.. daí senti um clima bem pesado e curti como esse clima e a atmosfera afetam o narrador.

Siker

Artista Comercial / Projetista Gráfico

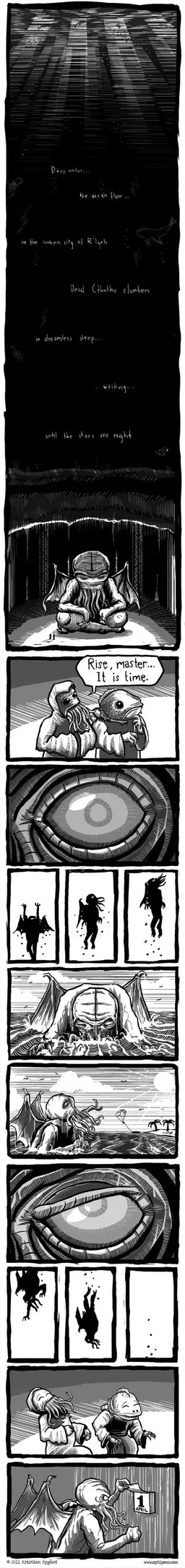

sitelovecraftEm "The Call of Cthulhu", Lovecraft dispôs os fundamentos de seu conceito mitológico. Ele disse que há muitos milênios atrás, os Grandes Antigos vieram de outros planetas e estabeleceram residência na Terra. Quando as estrelas estavam em posições erradas eles não podiam viver, assim eles desapareceram sob o oceano pacífico sul ou voltaram aos seus mundos de origem onde usaram poderes telepáticos, muitas vezes em sonhos para comunicar-se com o homem. Tema central ao mito de Lovecraft, os Antigos formaram um culto e uma religião que adorava os aliens como deuses. Nas histórias, os Antigos pairam a meio caminho entre puros extraterrestres e verdadeiros deuses, como requer o enredo. Em seu romance "Nas Montanhas da Loucura", ele escreveu que uma espécie dos Antigos criou o homem para servi-los, iniciando as primeiras civilizações humanas: Atlântida, Lemuria e Mu.

É isso o que eu acho interessante e que consegue me causar um pouco de medo e bastante tensão, a mitologia fantástica criada por Lovecraft é realmente fantástica, porém em Call of Cthulhu eu simplesmente não consegui enxergar o horror, gostei do início do conto justamente por detalhar este ambiente no qual o desconhecido se torna uma realidade nefasta, porém quando o personagem começa a narrar os acontecimentos do documento "CTHULHU CULT", a leitura fica mais difícil, em outras palavras, chata mesmo, eu não gostei de ler os acontecimentos daquela forma, os sonhos e todo o ocorrido são fatos interessantes, mas ler alguém lendo o que aconteceu, me deu sono.

A parte do Legrasse achei mais interessante que a primeira, mas também não o suficiente para prender completamente a minha atenção, já o final sim conseguiu alcançar algo, A Loucura Vinda do Mar mostrou mais detalhes sobre este lado sombrio da existência de R'lyeh e Cthulhu, mostrou o terror do personagem principal, e para mim foi o que valeu no conto. Pretendo ler outras histórias do Lovecraft para comparar sua escrita, pois pareceu que neste conto ele narrou com muito suspense e acabou perdendo o clímax de toda a ação, uma história magnificamente interessante não foi contada de uma forma interessante.

Gigio

Usuário

Na minha opinião, o conto tem sim bastante potencial de terror, só que nós, leitores de hoje, já estamos tão sobrecarregados de informações que acabamos perdendo a sensibilidade (como em tantas outras coisas). Nós já vimos horrores que vêm do espaço, que vêm da neve, que habitam o fundo do mar... Já vimos terror no cinema, em 3D, em jogos... Já vimos o Hellboy explodindo um "Cthulhu"! Acima disso ainda, acho que temos uma sensação de segurança muito grande, ao menos em relação ao sobrenatural. Se os seus avós são como os meus (foram), devem ser pessoas que não se sentem muito confortáveis com o uso de palavras como "demônio" ou "maldição". Eles são do tempo em que não se brincava com essas coisas, que é um tempo ainda mais recente que "O Chamado de Cthulhu". Para entrar mesmo no espírito do conto, hoje, é preciso relembrar a época em que fomos mais influenciáveis, como se fôssemos crianças ouvindo histórias de primos mais velhos durante um blecaute (nem blecaute quase não há mais por estes tempos). É preciso acreditar realmente na história, ao menos por um momento.

Para mim, o mais fantástico no conto foi esse primeiro parágrafo. A ideia é incrível e está muito bem formulada. Não acho que a tradução da Hedra tenha captado tão bem o espírito da prosa do Lovecraft. No original:

Serve também como princípio de estruturação do conto né, o leitor deveria ir juntando aos poucos as pistas até perceber, num súbito terror, as dimensões do que estaria oculto ali. Nesse sentido não sei a história é tão bem sucedida, acho que o leitor descobre muito rápido qual é o lance (embora isso também possa ser função daquela superexposição).

Só o final que, sinceramente, achei meio coisa de filme B. É só passar com o barco em cima do Cthulhu e, beleza, ele volta para a hibernação por mais alguns eons? :

Para mim, o mais fantástico no conto foi esse primeiro parágrafo. A ideia é incrível e está muito bem formulada. Não acho que a tradução da Hedra tenha captado tão bem o espírito da prosa do Lovecraft. No original:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Serve também como princípio de estruturação do conto né, o leitor deveria ir juntando aos poucos as pistas até perceber, num súbito terror, as dimensões do que estaria oculto ali. Nesse sentido não sei a história é tão bem sucedida, acho que o leitor descobre muito rápido qual é o lance (embora isso também possa ser função daquela superexposição).

Só o final que, sinceramente, achei meio coisa de filme B. É só passar com o barco em cima do Cthulhu e, beleza, ele volta para a hibernação por mais alguns eons? :

Última edição:

O principal do conto não o medo que ele pode causar no leitor, mas sim a criação da atmosfera na qual está envolta a história, e é nela que está o terror; e os personagens, por estarem dentro dessa atmosfera e a vivenciando em primeira (ou segunda, no caso do narrador) mão, são os principais afetados por ela, com consequências desastrosas, físicas e mentais. (Tema recorrente nos contos do Lovecraft: conhecimento demais sobre o que devia ser deixado quieto = perdição).

O terror está nessas descobertas mesmo.

Não é nem nas descrições das criaturas (horrendas e geralmente gigantescas) mas em descobrir coisas que nenhum ser humano jamais imaginou: que o ser humano não é a primeira forma de vida civilizada que surgiu na Terra; que outras criaturas, com aparência, inteligência e moral bem diferente da nossa habitou este planeta.

(...) e os personagens, por estarem dentro dessa atmosfera e a vivenciando em primeira (ou segunda, no caso do narrador) mão, são os principais afetados por ela, com consequências desastrosas, físicas e mentais. (Tema recorrente nos contos do Lovecraft: conhecimento demais sobre o que devia ser deixado quieto = perdição).

E uma coisa que eu acho engraçada (mesmo) nas histórias do Lovecraft são os pitís que alguns personagens dão.

Homens do mar, cientistas experientes, não importa, quase sempre tem um que, a certa altura, faz a louca e sai correndo arrancando os cabelos.

(...)Acima disso ainda, acho que temos uma sensação de segurança muito grande, ao menos em relação ao sobrenatural. Se os seus avós são como os meus (foram), devem ser pessoas que não se sentem muito confortáveis com o uso de palavras como "demônio" ou "maldição". Eles são do tempo em que não se brincava com essas coisas, que é um tempo ainda mais recente que "O Chamado de Cthulhu". Para entrar mesmo no espírito do conto, hoje, é preciso relembrar a época em que fomos mais influenciáveis, como se fôssemos crianças ouvindo histórias de primos mais velhos durante um blecaute (nem blecaute quase não há mais por estes tempos). É preciso acreditar realmente na história, ao menos por um momento.

E acreditamos que a ciência pode nos dar todas as respostas também. Tipo: "nós já sabemos de tudo. O que mais há prara se descobrir?" e aí aparece não só um mundo, mas vários mundos (no fundo do mar, na Antartida, no espaço, nos subterrâneos da cidade onde moramos) e o conhecimento humano vai todo por água abaixo.

Pode reparar que a maioria dos narradores/personagens principais das histórias do Lovecraft é de cientistas, professores ou alunos; é sempre alguém interessado em descobrir explicações para o que a maioria prefere fingir que não vê.

Só o final que, sinceramente, achei meio coisa de filme B. É só passar com o barco em cima do Cthulhu e, beleza, ele volta para a hibernação por mais alguns eons? :

É que o Lovecraft descartou uma parte do final, por achá-la anticlimax. Mas recentemente acharam uns manuscritos do homem de Providence onde se explica o motivo de Cthulhu ter voltado tão rápido pra o fundo do oceano:

Anexos

*Ceinwyn*

Ogra rosa

Não acho que o que me faz não gostar tanto do Lovecraft seja o tanto de "ultrapassado" que ele está. Poe e Stevenson são também do século XIX e seus contos e romances me transmitem o horror que o Lovecraft não me transmite, ou não me transmitiu até agora.

Outra coisa que me atrapalhou na leitura do Cthulhu foi a expectativa. Como é um grande clássico do Lovecraft, esperava ver algo que me surpreendesse, me causasse horror, algo que me fizesse querer mais de Lovecraft. A frustração fez o efeito oposto: larguei a edição da Hedra que tem o conto justamente porque me frustrei depois de pular alguns contos até chegar ao Cthulhu. Um dia volto ao livro, termino, mas sem pressa...

Esse tema é pouco interessante pra mim, me enjoou. Poucos são os contos dele que eu realmente gostei, exatamente porque não aguentava mais ver variações do mesmo tema, sendo de um tema que pouco me atrai.Tilion disse:Tema recorrente nos contos do Lovecraft: conhecimento demais sobre o que devia ser deixado quieto = perdição

Outra coisa que me atrapalhou na leitura do Cthulhu foi a expectativa. Como é um grande clássico do Lovecraft, esperava ver algo que me surpreendesse, me causasse horror, algo que me fizesse querer mais de Lovecraft. A frustração fez o efeito oposto: larguei a edição da Hedra que tem o conto justamente porque me frustrei depois de pular alguns contos até chegar ao Cthulhu. Um dia volto ao livro, termino, mas sem pressa...

Comecei a reler o conto aqui, e pensei num leve (bem leve) paralelismo entre a introdução e o conceito de singularidade tecnológica. Relembrando a introdução (que já foi postada acima tb):

O paralelo existe de maneira bem leve (até pq o contexto de aplicação do conceito de singularidade tecnológica é bem diferente), mas acho interessante traçar ao menos alguma coisa em comum: a ideia de que o avanço das ciências, em algum momento, nos levará ao um drástico ponto de inflexão na sociedade humana. Na obra de Lovecraft a visão é sempre pessimista e inserida num caráter místico/ocultista: o avanço científica é perigoso na medida que nos revela segredos ancestrais, e em um dado ponto a revelação nos levará a duas possibilidades: loucura ou retorno a uma idade das trevas, renegando a ciência. Já no conceito de singularidade tecnológica, a evolução não será necessariamente um mal (apesar de vários filósofos da ciência apontarem muito mais nessa direção), e o novo horizonte que se abrirá estará inteiramente ligado aos próprios produtos da ciência (superinteligência artificial, trans-humanidade etc.).

Como eu disse, o paralelo é bastante sutil, e basicamente reside num único ponto. Mas é interessante pensar as ideias em paralelo. De repente até pode ser inspiração para alguma obra de sci-fi de horror lovecraftiano.

-----

Outro ponto comum na obra do Lovecraft é o apelo dele à descrições que remetem ao "incerto", ao "desconhecido", ao "inimaginável", e assim por diante. Esses adjetivos são recorrentes na criação da atmosfera dos Cthulhu mythos. Pegando por exemplo um breve trecho na parte do relato do inspetor Legrasse (quase escrevi "Lagrange"... ê matemática):

"...cujos ares de antiguidade abismal traziam fortes indícios de panoramas desconhecidos e arcaicos. Nenhum escola conhecida de escultura havia animado aquele terrível objeto, mas o passar de séculos e talvez milênios parecia estar registrado na superfícia opaca e esverdeada de pedra indefinível."

"O próprio material era um mistério insondável; a rocha preto-esverdeada, com veios e listras dourados e iridescentes, não se assemelhava a nada conhecido pela geologia ou pela mineralogia."

Essas descrições desempenham o papel de dar consistência àquela noção lançada na introdução. A realidade do mundo ancestral dos Great Old Ones é desconhecida para a ciência humana, e então o desconhecido vem à tona justamente pelo fato de cientistas, pesquisadores e outras pessoas, eventualmente, travarem contato com artefatos e experiências relacionadas ao mundo ancestral. As próprias palavras Cthulhu, R'lyeh, fhtagn, são quase impronunciáveis e uma mera aproximação alfabética dos fonemas utilizados nos rituais tribais.

Bem, ainda não terminei a releitura, mais além devo fazer outras considerações aqui. Esse post foi mais para tirar o pó e ver se rolam mais colocações sobre o conto.

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

O paralelo existe de maneira bem leve (até pq o contexto de aplicação do conceito de singularidade tecnológica é bem diferente), mas acho interessante traçar ao menos alguma coisa em comum: a ideia de que o avanço das ciências, em algum momento, nos levará ao um drástico ponto de inflexão na sociedade humana. Na obra de Lovecraft a visão é sempre pessimista e inserida num caráter místico/ocultista: o avanço científica é perigoso na medida que nos revela segredos ancestrais, e em um dado ponto a revelação nos levará a duas possibilidades: loucura ou retorno a uma idade das trevas, renegando a ciência. Já no conceito de singularidade tecnológica, a evolução não será necessariamente um mal (apesar de vários filósofos da ciência apontarem muito mais nessa direção), e o novo horizonte que se abrirá estará inteiramente ligado aos próprios produtos da ciência (superinteligência artificial, trans-humanidade etc.).

Como eu disse, o paralelo é bastante sutil, e basicamente reside num único ponto. Mas é interessante pensar as ideias em paralelo. De repente até pode ser inspiração para alguma obra de sci-fi de horror lovecraftiano.

-----

Outro ponto comum na obra do Lovecraft é o apelo dele à descrições que remetem ao "incerto", ao "desconhecido", ao "inimaginável", e assim por diante. Esses adjetivos são recorrentes na criação da atmosfera dos Cthulhu mythos. Pegando por exemplo um breve trecho na parte do relato do inspetor Legrasse (quase escrevi "Lagrange"... ê matemática):

"...cujos ares de antiguidade abismal traziam fortes indícios de panoramas desconhecidos e arcaicos. Nenhum escola conhecida de escultura havia animado aquele terrível objeto, mas o passar de séculos e talvez milênios parecia estar registrado na superfícia opaca e esverdeada de pedra indefinível."

"O próprio material era um mistério insondável; a rocha preto-esverdeada, com veios e listras dourados e iridescentes, não se assemelhava a nada conhecido pela geologia ou pela mineralogia."

H.P. Lovecraft, O Chamado de Cthulhu e Outros Contos. Hedra, 2009, pp 111-12

Essas descrições desempenham o papel de dar consistência àquela noção lançada na introdução. A realidade do mundo ancestral dos Great Old Ones é desconhecida para a ciência humana, e então o desconhecido vem à tona justamente pelo fato de cientistas, pesquisadores e outras pessoas, eventualmente, travarem contato com artefatos e experiências relacionadas ao mundo ancestral. As próprias palavras Cthulhu, R'lyeh, fhtagn, são quase impronunciáveis e uma mera aproximação alfabética dos fonemas utilizados nos rituais tribais.

Bem, ainda não terminei a releitura, mais além devo fazer outras considerações aqui. Esse post foi mais para tirar o pó e ver se rolam mais colocações sobre o conto.

Mohanah

Usuário

Não acho que o que me faz não gostar tanto do Lovecraft seja o tanto de "ultrapassado" que ele está. Poe e Stevenson são também do século XIX e seus contos e romances me transmitem o horror que o Lovecraft não me transmite, ou não me transmitiu até agora.

Concordo plenamente. Nunca li Stevenson, mas sou grande fã de Poe.

Outra coisa que me atrapalhou na leitura do Cthulhu foi a expectativa. Como é um grande clássico do Lovecraft, esperava ver algo que me surpreendesse, me causasse horror, algo que me fizesse querer mais de Lovecraft. A frustração fez o efeito oposto: larguei a edição da Hedra que tem o conto justamente porque me frustrei depois de pular alguns contos até chegar ao Cthulhu. Um dia volto ao livro, termino, mas sem pressa...

Senti a mesma coisa, mas pretendo dar mais uma chance ao Lovecraft. lol

Agora vamos a minha opinião em si sobre a história.

Achei um desperdício de uma ideia foda. Não por acaso, todos conhecem o personagem, mas não a história. O narrador é chato demais e nada convincente. O cara começa totalmente cético e do nada se borra de medo do Cthulhu. Um conto fantástico precisa vender uma realidade, para depois introduzir o estranho/maravilhoso e te colocar naquela dúvida (essa é a alma do fantástico). Se a realidade não é bem construida, a dúvida não tem como existir. Na minha opinião, esse é o X da questão aqui.

E o que é aquele final? O bicho é derrotado por um barco? É a cereja do bolo de um texto absolutamente mal estruturado, uma narrativa corrida que não sabe que caminho seguir.

Esqueci de voltar aqui depois que terminei o conto

Mas sem grandes acréscimos, a não ser para comentar sobre as opiniões das pessoas que se frustraram com o final do conto. O lance do barco "vencendo" o Cthulhu pode parecer frustrante e implausível para muitos. De certa forma, até eu achei isso. Mas acho que a sacada desse final não está em parecer plausível ou não, mas sim em mostrar que é factível, dentro dos mythos, o retorno dos Great Old Ones ao mundo. E se Cthulhu foi derrotado, é apenas em caráter temporário. Ele continua esperando em R'lyeh, e a cada novo momento em que os astros colaborarem, haverá cultistas prontos para trazê-lo de volta. O mal não pode ser completamente derrotado. Ele permanece, e a mera possibilidade de Cthulhu retornar deve criar grandes temores nas pessoas que, inadvertidamente ou não, trava algum nível de contato com a "verdade do mundo antigo".

No mais, como exercício de imaginação, até dá para encontrar alguns argumentos que tornam a derrota do Cthulhu mais aceitável. Por exemplo, ele poderia estar enfraquecido pelos milênios em que passou preso, e logo após ser libertado ainda não tinha condições de atingir full power. Ou talvez as circunstâncias de sua libertação não tenham sido as mais propícias em termos de alinhamentos dos astros. Enfim, meras conjecturas, até pq acho que não faz muito sentido tentar achar uma lógica para isso.

Ah, e a título de curiosidade, já procuraram onde fica R'lyeh? Dadas as coordenadas no conto, basta jogar no google maps e tchuns! O lugar onde R'lyeh jaz sob as águas!

Mas sem grandes acréscimos, a não ser para comentar sobre as opiniões das pessoas que se frustraram com o final do conto. O lance do barco "vencendo" o Cthulhu pode parecer frustrante e implausível para muitos. De certa forma, até eu achei isso. Mas acho que a sacada desse final não está em parecer plausível ou não, mas sim em mostrar que é factível, dentro dos mythos, o retorno dos Great Old Ones ao mundo. E se Cthulhu foi derrotado, é apenas em caráter temporário. Ele continua esperando em R'lyeh, e a cada novo momento em que os astros colaborarem, haverá cultistas prontos para trazê-lo de volta. O mal não pode ser completamente derrotado. Ele permanece, e a mera possibilidade de Cthulhu retornar deve criar grandes temores nas pessoas que, inadvertidamente ou não, trava algum nível de contato com a "verdade do mundo antigo".

No mais, como exercício de imaginação, até dá para encontrar alguns argumentos que tornam a derrota do Cthulhu mais aceitável. Por exemplo, ele poderia estar enfraquecido pelos milênios em que passou preso, e logo após ser libertado ainda não tinha condições de atingir full power. Ou talvez as circunstâncias de sua libertação não tenham sido as mais propícias em termos de alinhamentos dos astros. Enfim, meras conjecturas, até pq acho que não faz muito sentido tentar achar uma lógica para isso.

Ah, e a título de curiosidade, já procuraram onde fica R'lyeh? Dadas as coordenadas no conto, basta jogar no google maps e tchuns! O lugar onde R'lyeh jaz sob as águas!

Eu não me preocupo com esse negócio de os contos do Lovecraft serem ou não assustadores.

Pra falar a verdade, consigo me lembrar só de duas histórias que li e me deixaram assustada, nenhuma delas era do Lovecraft.

O que me impressiona nas histórias do homem de Providence é o clima e a descoberta de coisas e seres tão distantes e ao mesmo tempo tão próximos de nós, de nossa vida normal.

Tanto que minhas histórias favoritas do Lovecraft são "A Sombra Sobre Innsmouth" e "A Casa das Bruxas", exatamente pela ideia que elas sugerem, de coisas aparentemente banais como um quarto em uma casa antiga ou uma visita a uma cidade decadente num passeio de verão, serem vias de acesso a mistérios inomináveis e além da imaginação humana.

Pra falar a verdade, consigo me lembrar só de duas histórias que li e me deixaram assustada, nenhuma delas era do Lovecraft.

O que me impressiona nas histórias do homem de Providence é o clima e a descoberta de coisas e seres tão distantes e ao mesmo tempo tão próximos de nós, de nossa vida normal.

Tanto que minhas histórias favoritas do Lovecraft são "A Sombra Sobre Innsmouth" e "A Casa das Bruxas", exatamente pela ideia que elas sugerem, de coisas aparentemente banais como um quarto em uma casa antiga ou uma visita a uma cidade decadente num passeio de verão, serem vias de acesso a mistérios inomináveis e além da imaginação humana.

Ilmarinen

Usuário

Cabe aqui salientar que um dos motivos pra que Call of Cthulhu não seja um indutor de medo tão grande quanto o era na década de vinte é o fato dele já ter sido satirizado e "pasteurizado", virado "lugar comum", servindo de base pra um sem número de adaptações e cópias do original. Aí a idéia, quando chega aos leitores atuais, parece uma coisa já meio batida e "clichê", sendo que Lovecraft foi, praticamente, o criador do trope "mal selado, esperando pra acordar".

Uma vez que minhas particulares contribuições acerca do Conto que, junto com Nas Montanhas da Loucura e Charles Dexter Ward tende a ser meu Lovecraft favorito já foram, pertinente e oportunamente, repostadas aqui pelo nosso amigo Siker, lembrando a noção de que JRRT também pode constar da lista dos influenciados pelo escritor de

Providence, só me resta compartilhar alguns easter eggs interessantes que não são de conhecimento geral.

Em primeiro lugar, Call of Cthulhu foi homenageado no desenho dos Caça-Fantasmas dos anos 80 pelo escritor dos melhores episódios de Caverna do Dragão, o Michael Reaves.

Taí o danado.

Taí o danado.

Na Marvel, o Cthulhu é inspiração visual e conceitual pra, pelo menos, 5 grandes personagens

Demogorge, a forma "devoradora de deuses" de Atum, o primeiro filho da Deusa Gaia

Cyttorak, o patrono do Fanático ( Juggernaut)

Tiamut- O Celestial Negro ( Dreaming Celestial), criado por Jack Kirby "coincidentemente" no mesmo ano de publicação do Silmarillion de Tolkien.

Condenado pelos seus Pares Celestiais a ser enterrado na Terra depois da Segunda Expedição dos Celestiais por ter cometido "um crime contra a própria "Vida", e, em uma versão pelo menos, ter sido responsável pela "criação" dos Deviantes, lembrando Melkor com seu crime de ter criado os Orcs, o Dreaming Celestial emite, a la Cthulhu, emanação via onírica para seus comandados deviantes com o fito de, um dia, ser libertado, "despertar" e recuperar o que seria seu por direito.

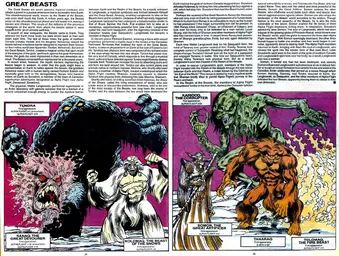

Tundra-uma das Sete Grandes Feras

Banido junto com seus irmãos pelos deuses inuits ( esquimós) liderados por Hodiak e Nelvanna que se sacrificaram pra fazer tal feito que resultou no banimento de ambos os panteões de "deuses", bons e maus, pra planos de existência adjacentes, ficando retidos lá por barreiras místicas erigidas pelos parentes da Pássaro da Neve, cujo verdadeiro nome é Narya (o mesmo do anel de fogo de Gandalf).

A Grande Família das Grandes Bestas

Meu primeiro "Cthulhu genérico", apresentado na história original da Tropa Alfa que lançou o título da equipe, criado pelo "endiabrado John Byrne" ( e, sim, eu tive medo pra caramba!!).

Também vejam só o que John Byrne aprontava

Tinha o toque interessante de, além de ser despertado por ritual mágico envolvendo o sacrifício de uma centelha de vida humana, ser conectado misticamente à própria terra do Canadá, mais ou menos como acontecia com Morgoth na descrição do Anel de Morgoth, HoME X. O ataque contra o gigante abalava toda a massa continental da América Setentrional assim como o ataque contra Morgoth pelo exército dos Valar redundou no afundamento de Beleriand no mar.

Chthon, o Necromante, Senhor do Caos

O responsável pelos poderes místicos da Feiticeira Escarlate e, no fim das contas, pela criação dos vampiros, lobisomens e demais monstros do Universo Marvel. Deixou como memento em nossa dimensão, depois de banido pelo primeiro dessa lista , o seu sobrinho Demogorge, filho da irmãzinha protetora de primatas, Gaia, um livro "indestrutível e escrito com letras de fogo" que tem vontade própria, comanda quem tenta

controlá-lo numa corrupção irresistível( epa!!) ( lembrando um combo do Anel do Poder de Tolkien com o Necronomicon do Lovecraft) e contém os feitiços mais poderosos e profanos de todo o Marvel Universe (incusive a fórmula do encantamento que pode destruir TODOS os vampiros da Terra, utilizada (mal e porcamente com uma explicação "científica" rastaquera) no último filme de Blade), o famigerado Tomo Negro.

Uma das experienciazinhas de Chthon na dimensão pra onde foi exilado resultou na criação dos N'garai, inimigos dos X-Men, os aliens cover da Marvel, que também são"Deuses Negros" por sua própria conta.

Esse também tem a peculiaridade de ser uma versão hiperdark do Tom Bombadil e seu poder de nomeação, controle e "m(a)estria" sobre a ordem natural

Oldest and Fatherless: The Terrible Secret of Tom Bombadil

BRRRRRrrrr, confesso que, dos análogos cthulhianos acima, Chthon é que , modernamente, continua a me meter mais medo e que não foi, apesar de algumas tentativas, meio que diminuído pelos caprichos dos escritores da Marvel.

Segundo a opinião de alguns é, de longe, o Demônio-Mor do Universo Marvel

Uma vez que minhas particulares contribuições acerca do Conto que, junto com Nas Montanhas da Loucura e Charles Dexter Ward tende a ser meu Lovecraft favorito já foram, pertinente e oportunamente, repostadas aqui pelo nosso amigo Siker, lembrando a noção de que JRRT também pode constar da lista dos influenciados pelo escritor de

Providence, só me resta compartilhar alguns easter eggs interessantes que não são de conhecimento geral.

Em primeiro lugar, Call of Cthulhu foi homenageado no desenho dos Caça-Fantasmas dos anos 80 pelo escritor dos melhores episódios de Caverna do Dragão, o Michael Reaves.

Na Marvel, o Cthulhu é inspiração visual e conceitual pra, pelo menos, 5 grandes personagens

Demogorge, a forma "devoradora de deuses" de Atum, o primeiro filho da Deusa Gaia

Cyttorak, o patrono do Fanático ( Juggernaut)

Tiamut- O Celestial Negro ( Dreaming Celestial), criado por Jack Kirby "coincidentemente" no mesmo ano de publicação do Silmarillion de Tolkien.

Condenado pelos seus Pares Celestiais a ser enterrado na Terra depois da Segunda Expedição dos Celestiais por ter cometido "um crime contra a própria "Vida", e, em uma versão pelo menos, ter sido responsável pela "criação" dos Deviantes, lembrando Melkor com seu crime de ter criado os Orcs, o Dreaming Celestial emite, a la Cthulhu, emanação via onírica para seus comandados deviantes com o fito de, um dia, ser libertado, "despertar" e recuperar o que seria seu por direito.

Tundra-uma das Sete Grandes Feras

Banido junto com seus irmãos pelos deuses inuits ( esquimós) liderados por Hodiak e Nelvanna que se sacrificaram pra fazer tal feito que resultou no banimento de ambos os panteões de "deuses", bons e maus, pra planos de existência adjacentes, ficando retidos lá por barreiras místicas erigidas pelos parentes da Pássaro da Neve, cujo verdadeiro nome é Narya (o mesmo do anel de fogo de Gandalf).

A Grande Família das Grandes Bestas

Meu primeiro "Cthulhu genérico", apresentado na história original da Tropa Alfa que lançou o título da equipe, criado pelo "endiabrado John Byrne" ( e, sim, eu tive medo pra caramba!!).

Também vejam só o que John Byrne aprontava

Tinha o toque interessante de, além de ser despertado por ritual mágico envolvendo o sacrifício de uma centelha de vida humana, ser conectado misticamente à própria terra do Canadá, mais ou menos como acontecia com Morgoth na descrição do Anel de Morgoth, HoME X. O ataque contra o gigante abalava toda a massa continental da América Setentrional assim como o ataque contra Morgoth pelo exército dos Valar redundou no afundamento de Beleriand no mar.

Chthon, o Necromante, Senhor do Caos

O responsável pelos poderes místicos da Feiticeira Escarlate e, no fim das contas, pela criação dos vampiros, lobisomens e demais monstros do Universo Marvel. Deixou como memento em nossa dimensão, depois de banido pelo primeiro dessa lista , o seu sobrinho Demogorge, filho da irmãzinha protetora de primatas, Gaia, um livro "indestrutível e escrito com letras de fogo" que tem vontade própria, comanda quem tenta

controlá-lo numa corrupção irresistível( epa!!) ( lembrando um combo do Anel do Poder de Tolkien com o Necronomicon do Lovecraft) e contém os feitiços mais poderosos e profanos de todo o Marvel Universe (incusive a fórmula do encantamento que pode destruir TODOS os vampiros da Terra, utilizada (mal e porcamente com uma explicação "científica" rastaquera) no último filme de Blade), o famigerado Tomo Negro.

Uma das experienciazinhas de Chthon na dimensão pra onde foi exilado resultou na criação dos N'garai, inimigos dos X-Men, os aliens cover da Marvel, que também são"Deuses Negros" por sua própria conta.

Esse também tem a peculiaridade de ser uma versão hiperdark do Tom Bombadil e seu poder de nomeação, controle e "m(a)estria" sobre a ordem natural

Oldest and Fatherless: The Terrible Secret of Tom Bombadil

A long time ago, when the world was so new nothing had a name, something woke up. It learned all about what was and what would be... but most of all it learned what couldn't be, what shouldn't be. And it gave those things names, names it wrote on indestructible pages, because a namer has mastery of the named.

BRRRRRrrrr, confesso que, dos análogos cthulhianos acima, Chthon é que , modernamente, continua a me meter mais medo e que não foi, apesar de algumas tentativas, meio que diminuído pelos caprichos dos escritores da Marvel.

Segundo a opinião de alguns é, de longe, o Demônio-Mor do Universo Marvel

Nota tolkieniana coincidental obrigatória:

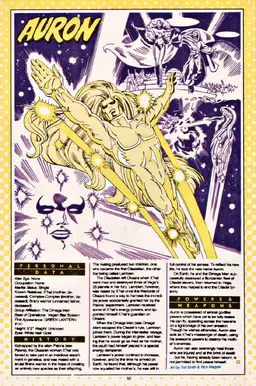

A forma "deus solar" do Demogorge, o Atum, muito estranhamente, já que o personagem foi criado 11 anos antes de HoME X sair, tem um paralelismo ENORME com a história tardia do Tulkas, revelada por Tolkien em HoME X, onde ele era chamado Auron, e era um vala do fogo e do sol. O nome Auron também, coincidentemente, ( até onde sabemos, é coincidência; o Auron da DC apareceu em 1981, o HoME X contando a história "solar" de Tulkas saiu em 1993) relembra um personagem da DC ( na verdade dois personagens) com características também semelhantes ao Atum.

Comentado e analisado aí nessa citação brilhante analisando a evolução de Tulkas com a menção por extenso do texto de HoME ( especulações MUITO INTERESSANTES que refletem algumas idéias e cogitações que eu mesmo já fiz)

6. Tolkien then reassesses Tulkas, ever Morgoth’s chief adversary:

“It was in the wielding of flame that Tulkas (? Originally Vala of the Sun) defeated him in the First Battle. Melkor therefore comes mostly at night and especially to the North in winter. (It was after the First Battle that Varda set certain stars as ominous signs for the dwellers in Arda to see)…

[If Tulkas came from the Sun, then Tulkas was the form this Vala adopted on Earth, being in origin Auron (masculine). But the Sun is feminine; and it is better that the Vala should be Áren, a maiden whom Melkor endeavoured to make his spouse (or ravished); she went up in flame of wrath and anguish and her spirit was released from Eä, but Melkor was blackened and burned, and his form was thereafter dark, and he took to darkness. (The Sun itself was Anar neuter or Úr, cf. Rana, Ithil)] [HoMe10,376].

7. Finally, near 1960, Tolkien came up with this original Valarin meaning for the name of Tulkas, which he had previously translated in Quenya as “strong, immoveable, steadfast”:

“V Tulukhastáz; said to contain V elements tulukha(n) ‘yellow’, and (a)sata- ‘hair of head’: ‘the golden-haired’.” [HoMe5,395; HoMe11,399]

Anexos

Última edição:

Ilmarinen

Usuário

Comemorando o post número 500.

Texto dele comentando o débito pra Teosofia aí

http://crypt-of-cthulhu.com/lovecrafttheosophy.htm

Esse outro aí analisa as correspondências com o sistema mágico e a cosmologia de Aleister Crowley

Traduzi uma nota introdutória do conto escrita por S. T. Joshi (o maior especialista em Lovecraft) e publicada em The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories, da editora Penguin. Quem souber inglês e quiser ter as edições definitivas dos contos do Lovecraft, esse volume e os outros dois (The Thing on the Doorstep and Other Weird Stories e The Dreams in the Witch House and Other Weird Stories), todos editados por Joshi, são essenciais, com inúmeras informações bio-bibliográficas em centenas de notas, além de os textos dos contos terem sido corrigidos por Joshi, deixando-os como deveriam ter sido publicados originalmente (praticamente todas as edições de contos de Lovecraft até então possuíam inúmeros erros tipográficos).

Robert M. Price aponta outra influência significativa no conto – a teosofia. O movimento teosófico começou com Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, cujas obras Ísis sem véu (1877) e A Doutrina Secreta (1888-1897) introduziram no Ocidente essa mistura peculiar de ciência, misticismo e religião. Lovecraft obviamente não acreditava na teosofia, mas considerava muitas das especulações cósmicas da doutrina estimulantes para a imaginação.

Texto dele comentando o débito pra Teosofia aí

http://crypt-of-cthulhu.com/lovecrafttheosophy.htm

Esse outro aí analisa as correspondências com o sistema mágico e a cosmologia de Aleister Crowley

Lovecraft: Al Azif The Book of the Arab; Crowley: Al vel Legis, The Book of the Law.

Lovecraft: The Great Old Ones; Crowley: The Great Ones of the Night Time.

Lovecraft: Yog-Sothoth; Crowley: Sut-Thoth, Sut-Typhon.

Lovecraft: Gnoph-Hek (The Hairy Thing); Crowley: Coph-Nia (a barbarous name in Liber vel Legis).

Lovecraft: The Cold Waste (Kadath); Crowley: The Wanderer of the Waste (Hadith).

Lovecraft: Nyarlathotep (a god accompanied by ‘idiot flute players’). Crowley: ‘Into my loneliness comes the sound of flutes’, Liber VII).

Lovecraft: The overpowering stench associated with Nyarlathotep; Crowley: ‘The perfume of Pan pervading ‘ (Liber VII).

Lovecraft: Great Cthulhu dead, but dreaming in R’lyeh. Crowley: The Primal Sleep, ‘In which the Great Ones of the Night time are immersed’.

Lovecraft: Azathoth (‘the blind and idiot chaos at the centre of infinity’). Crowley: Azoth, the alchemical solvent; ‘Thoth, Mercury: Chaos is Hadit at the centre of Infinity (Nuit)’.

Lovecraft: The Faceless One (The God Nyarlathotep); Crowley: The Headless One.

Lovecraft: The five pointed star carven of grey stone; Crowley: Nuit’s Star: the five pointed star with the circle in the middle. Grant explains: ‘Grey is the colour of Saturn, the Great Mother of which Nuit is a form’. (57)

Of these correspondences, however forced they appear to the non-adept, Grant states:

The table is interesting because it shows how similarly and yet how differently related were certain archetypal patterns characteristic of the New Aeon. But whereas to Crowley the motifs conveyed no moral message, to Lovecraft they were instinct with horror and evil.(58)

Lovecraft's Use of Theosophy

by Robert M. Price

copyright © 1982 by Robert M. Price

reprinted by permission of Robert M. Price

Fritz Leiber ("John Carter: Sword of Theosophy", in DeCamp (ed. ), The Spell of Conan) traces HPB's influence on Edgar Rice Burroughs, and Lin Carter names H. P. Lovecraft as another of her debtors. Robert Turner (writing in The Necronomicon, The Book of Dead Names, pp. 66-67) also discerns theosophical currents in Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos. HPL certainly did borrow from HPB, but to our knowledge, no one has yet demonstrated the real extent of that influence. In the present article, we will show that several obscure passages in Lovecraft's work can be elucidated by reference to the lore of Theosophy.Encountering TheosophyIn his book Occult Philosophy, Marc Edmund Jones comments with some irony that despite Lovecraft's total disbelief in the occult, "His Cthulhu mythology is a complete and thoroughly rounded out job of invention, actually much more convincing than Leadbeater and Besant's presumably literal account of remote things in Man, Whence, How and Whither" (p. 89). He makes reference to Charles G. Leadbeater and Annie Besant, two of the principal leaders of Theosophy after Madame Blavatsky's death. Jones's statement is all the more ironic since HPL's "Cthulhu mythology" may be shown to derive, at least in some details, from the self-same Theosophical system.

In a letter to Clark Ashton Smith, Lovecraft reveals his acquaintance with Theosophy. "I've . . . been digesting something of vast interest as background or source material --- . . . i.e., the Atlantis-Lemuria tales, as developed by modern occultists & the[o]sophical charlatans. . . . What I have read is The Story of Atlantis and the Lost Lemuria, by Scott Elliott [sic]" (Selected Letters, vol. II, p. 58). Writing to Willis Conover, Lovecraft is even more frank. "The crap of the theosophists, which falls into the class of conscious fakery, is interesting in spots" (Lovecraft at Last, p. 33).

However, it appears that Lovecraft's explicit familiarity with Theosophy was somewhat limited. In a second letter to Smith, he mentions several new (Theosophical) mythologoumena and bemoans his ignorance of their source.[E. Hoffmann] Price has dug up another cycle of actual folklore involving an allegedly primordial thing called The Book of Dzyan, which is supposed to contain all sorts of secrets of the Elder World before the sinking of . . . Atlantis . . . and . . . Lemuria. . . . It is kept at the Holy City of Shamballah, and is regarded as the oldest book in the world --- its language being Senzar (ancestor of Sanscrit), which was brought to earth 18,000,000 years ago by the Lords of Venus. I don't know where E. Hoffmann got hold of this stuff, but it sounds damn good" (Selected Letters, vol. IV, p. 155).If he didn't know the origin of this material, at least he suspected, and correctly. In a letter to Price, he asks of this legend cycle, "What --- if any --- special cult (like the theosophists, who have concocted a picturesque tradition of Atlantean-Lemurian elder world stuff) . . . cherishes it?" (Selected Letters, vol. IV, p. 153) In a disarmingly frank statement, which we may suspect was intended as a knowing "wink" to the reader, Blavatsky herself had declared, "The reader is . . . invited to regard all that which follows as a fairy tale, if he likes. . . ." (An Abridgement of 'The Secret Doctrine', p. 17.) Lovecraft, in effect, accepted this invitation.The Book of DzyanIn many of his tales, Lovecraft has a protagonist stumble upon a secret cache of musty occult books, among which are usually to be found, The Book of Eibon, Prinn's De Vermis Mysteriis, D'erlette's Cultes de Goules, Von Junzt's Unaussprechlichen Kulten, and of course the Necronomicon of Abdul Alhazred. Occasionally, there are substitutions or additions to this checklist. One such optional item is The Book of Dzyan. In "The Haunter of the Dark" Robert Blake finds a copy among the books in the Starry Wisdom library.They were the black, forbidden things which most sane people have never even heard of, or have heard of only in furtive, timorous whispers; the banned and dreaded repositories of equivocal secrets and immemorial formulae which have trickled down the stream of time from the days of man's youth, and the dim, fabulous days before man was.The "big five" are listed. "But there were others he had known merely by reputation or not at all --- the Pnakotic Manuscripts, the Book of Dzyan. . . ." In "The Diary of Alonzo Typer", said diarist recounts how "I learned of The Book of Dzyan, whose first six chapters antedate the Earth. . . . " Lovecraft's successors continued to use the book in this kind of setting. In The Lurker at the Threshold, Derleth's narrator recalls that "I dipped into [the] strange and terrible pages" of the usual Mythos grimoires, plus "the Book of Dzyan, the Dhol Chants, and the Seven Cryptical Books of Hsan. I read of terrible and blasphemous cults of ancient, pre-human eras. . . ."

What was this Book of Dzyan? Could it live up to the shudder some reputation thus established for it? On the very first page of The Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky describes it as "An ancient manuscript --- a collection of palm leaves made impermeable to water, fire, and air, by some specific unknown process. . . . " (p. 1.) The name itself, "Dzyan", seems to represent the Sanskrit dhyana ("meditation"), the root of the Chinese Ch'an and the Japanese Zen. As DeCamp says, it is pronounced something like "John". Furthermore,Tradition says that it was taken down in Senzar, the secret sacerdotal tongue, from the words of the Divine Beings, who dictated it to the sons of Light, in Central Asia, at the very beginning of the [human] race. . . . The old book, having described Cosmic Evolution and explained the origin of everything on earth, including physical man, . . . goes no further. It stops short . . . just about 4989 years ago. . . . (The Secret Doctrine, vol. 1, p. xliii)More about these "Divine Beings" and "sons of Light" presently, but for now suffice it to note the close parallel between Lovecraft's reference to Dzyan in one of his letters quoted above, and this quote from The Secret Doctrine. Apparently, Price had quoted this text pretty much verbatim, as did HPL when he in turn related the material to Smith.

In fact, no such book exists. Or, one might better say, it is a pseudepigraph. Interested readers may obtain a copy of the text for themselves, but its origin is considerably more recent than that claimed for it by Madame Blavatsky. DeCamp points out the dependence of part of Dzyan on the Rig Veda's "Hymn of Creation" (Lost Continents, p. 60). Rene Guenon traces it to fragments of the Kanjur and Tanjur texts of Tibet (Robert S. Ellwood, Jr., Religious and Spiritual Groups in Modern America, p. 129). Finally, Gershorn G. Scholem makes a good case for the origin of Dzyan being an Aramaic kabbalistic text, the Sifra Di-Tseniutha, to which Blavatsky actually referred, transliterating its title as "Sifra Dzeniuta", a form even closer to "Dzyan" (Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, pp. 398-399).

The resultant Book of Dzyan or Stanzas of Dzyan (HPB used both titles interchangeably) was the core of the encyclopedic work The Secret Doctrine. The latter, in fact, purports to be but a massive commentary on the former. And though it is there made the centerpiece of a confusing jungle of obtuse speculation, the allegedly primordial text could hardly have accounted for the flabbergasted trauma of Alonzo Typer: "what I read will cloud and make horrible whatever period of life lies ahead of me."ShamballahIn the letter quoted above, Lovecraft refers to "the Holy City of Shamballah". Despite his manifest enthusiasm for "that Dzyan-Shamballah stuff", the mythical city appears but once in his fiction. We must refer again to "The Diary of Alonzo Typer", where the narrator recounts: "I learned of the city Shamballah, built by the Lemurians fifty million years ago, yet inviolate still behind its walls of psychic force in the eastern desert." The business about the Lemurians represents creative license, but the rest of the passage does stem from theosophical beliefs about the lost city.

Shamballah, the prototype for the fictional "Shangri-La", was believed by Theosophists to be "the spiritual center of the world and the original source of the secret doctrines of Theosophy" (Edwin Bernbaum, The Way to Shambhala, p. 20). Certain highly advanced "Masters" or "Mahatmas" (notably the Tibetan supermen Kuthumi and Morya El), from whom Blavatsky, A. P. Sinnett, and other early Theosophists claimed to receive telepathic revelations, were believed to dwell there. Surely these Masters supplied the prototype for "the undying leaders of the [Cthulhu] cult in the mountains of China", mentioned in "The Call of Cthulhu" just a line or two before an explicit reference to "the speculations of theosophists".

According to indigenous Tibetan legend, Shamballah is a hidden, ageless kingdom surrounded by a ring of impenetrable mountain peaks. It is ruled by a line of righteous philosopher-kings who preserve Buddhist culture and doctrine against the day when the outside world will have sunk completely into the mire of warfare and materialism. At this time, a messianic king will lead his army forth from the hidden city to destroy the wicked and establish a golden age (Bernbaum, p. 4).

According to indigenous Tibetan legend, Shamballah is a hidden, ageless kingdom surrounded by a ring of impenetrable mountain peaks. It is ruled by a line of righteous philosopher-kings who preserve Buddhist culture and doctrine against the day when the outside world will have sunk completely into the mire of warfare and materialism. At this time, a messianic king will lead his army forth from the hidden city to destroy the wicked and establish a golden age (Bernbaum, p. 4).

Tibetans believe that Shamballah is somewhere north of Tibet, in the Kunlun Mountains, or in Mongolia, the Sinkiang Province of China, or Siberia. Others suggest the North Pole or even another planet! Historians and mythographers, on the other hand, have suggested that if the legend has any basis, Shamballah may correspond to the Tarim Basin, West Turkestan, the ancient Kushan Empire, the Greek Kingdom of Bactria, theYarkand, Kashgar, or Khotan oases, or, finally, the old Uighur Kingdom of Khocho [= "Tcho-tcho"?] in the Turfan Depression beneath the Tien Shan Mountains (Bernbaum, p. 46). Probably the most attractive guess, however, is that of Idries Shah, who believes that "it could be derived from Shams-i-Balkh, the Bactrian Sun Temple, the ruins of which can still be seen at Balkh near the northern frontier of Afghanistan" (J. G. Bennett, Gurdjieff: Making a New World, p. 26).

What of HPL's reference to "inviolate . . . walls of psychic force"? Shamballah is often represented in Tibetan Buddhist lore as a symbol for the object of spiritual quest, like "the Celestial City" in Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress. Those who are unworthy can never find their way to Shamballah. To them, the city will remain invisible because their bad karma will "have created illusions that obscure [their] vision and prevent them from recognizing or seeing the Kingdom" (Bernbaum, p. 39). Lovecraft apparently had something like this in mind.

Incidentally, quests for Shamballah were not restricted to the realm of legend. Artist and occultist Nicholas Roerich, to whose "strange and disturbing Asian paintings" HPL refers in At the Mountains of Madness, undertook the journey in 1934. But he returned home empty handed. Even though Roerich had founded his own theosophical cult, the Roerich Foundation, he mustn't have had the spiritual wherewithal needed to penetrate that karmic curtain.The Lords of VenusIn the same context with The Book of Dzyan and the lost city of Shamballah, Lovecraft makes an enigmatic reference to "the Lords of Venus". ("I'm quite on edge about that Dzyan-Shamballah stuff. The cosmic scope of it --- Lords of Venus, and all that --- sounds so especially and emphatically in my line!") (Selected Letters, vol. IV, p. 153.) In the letter to Smith, he says the Senzar language, in which Dzyan was written, "was brought to earth . . . by the Lords of Venus." In "The Diary of Alonzo Typer", he says that The Book of Dzyan "was old when the lords of Venus came through space in their ships to civilize our planet." Finally, in "Through the Gates of the Silver Key" (rewritten from "Lord of Illusions" by E. Hoffmann Price, who "turned him on" to "that Dzyan-Shamballah stuff" to begin with), we read that "The Children of the Fire Mist came to Earth to teach the Elder Lore to man." These "children of the Fire Mist" correspond to the "Lords of Venus", but all this is going to take a bit of explaining.

The basic cosmological doctrine of Theosophy is that universal history may be divided into an infinite series of manvantaras, or cosmic-evolutionary aeons, separated by pralayas, or age-long periods of dormancy. At the start of each manvantara, Being-itself (Brahman), symbolized as Primordial Fire, begins to differentiate itself into individual beings. The first of these are seven solar deities, also called "Sons of the Fire Mist" because of their immediate derivation from it. (Secret Doctrine, vol. 1, p. 86.) The term also refers to "a group of semi-divine and semi-human beings" who incarnate these mighty entities on earth. They "become, from the first awakening of human consciousness, the guides of early Humanity. It is through these 'Sons of God' that infant humanity got its first notions of all the arts and sciences, as well as of spiritual knowledge" (Ibid., pp. 207,208). "It was they who imparted Nature's most weird secrets to men, and revealed to them the ineffable, and now lost 'word'" (Secret Doctrine, vol. 2, p. 220). This last is undoubtedly the "Elder Lore" mentioned by Lovecraft.

But where is the connection to Venus? In Scott-Elliot's The Story of Atlantis and the Lost Lemuria, the author, an orthodox Theosophist, explains that these primeval guides of humanity came to earth from Venus, whose cycle of evolution was advanced beyond that of earth. In fact, humanoid life on earth (on Lemuria, to be exact) was barely sentient. The Venusian Lords of the Fire Mist educated humanity in the first instance by psychically occupying their bodies and, as it were, "getting them used to" housing real intelligence, which they would then begin to develop on their own, by a kind of metaphysical Lamarckianism. How could the Venusians do this? They were "endowed with the stupendous powers of transferring their consciousness from the planet Venus to this our earth" (Scott-Elliot, p. 107). The "space-ships", then, are an addition by Lovecraft, since Theosophy's Venusians had no need of them.

If HPL did not retain Scott-Elliot's idea of mind-projection across space in connection with his "Lords of Venus", he did make use of the notion elsewhere. The Great Race of Yith in "The Shadow Out of Time" had projected their minds across time and space to inhabit the cone-shaped monstrosities of prehistoric Australia, much as the Theoaophical Venusians had incarnated themselves in the equally repugnant Lemurians. We may strongly suspect that the whole idea of the former was derived from the latter. In one letter, Lovecraft remarked, "Some of these hints about . . . the shapeless monsters of archaic Lemuria are ineffably pregnant with fantastic suggestion. . . ." Whence these hints? "What I have read is The Story of Atlantis and the Lost Lemuria. . . ." Specifically, Lovecraft must have had in mind Scott-Elliot's reference on p. 87: "Somewhat before the middle of the Lemurian period . . . the gigantic gelatinous body began slowly to solidify. . . ." So "The Shadow Out of Time"'s idea of advanced intellects from outer space teleporting to earth to inhabit primitive, gigantic, rubbery bodies seems to stem from HPL's reading of Scott-Elliot. He even supplies a fairly clear hint in this direction in that very story. As the narrator pours over ancient texts in order to reconstruct the history of the Great Race, he notices that "A few of the myths had significant connections with other cloudy legends of the prehuman world, especially those Hindu tales involving stupefying gulfs of time and forming part of the lore of modern theosophists."

From the Theosophists, too, Lovecraft seems to have derived his ubiquitous references to "cyclopean" ruins, denoting the past dominance of gigantic alien races, such as those just described. In "Out of the Eons", a "gigantic fortress of Cyclopean stone" is attributed to "the alien spawn of the dark planet Yuggoth, which had colonized the earth before the birth of terrestrial life." In "The Call of Cthulhu", Wilcox dreams of "the damp Cyclopean city of slimy green stone. . . . The size of the Old Ones [who built the city of R'lyeh], he curiously declined to mention." In The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath, Randolph Carter wonders at "the vast clay-brick ruins of a primal city whose name is not remembered." He "did not like the size and shape of the ruins. . . . And what the structure and proportions of the olden worshippers could have been, Carter steadily refused to conjecture."

The Theosophists were not so reticent as Wilcox and Carter, however. Madame Blavatsky declares that "cyclopean ruins and colossal stones [are] witnesses to giants. . . . We say that most of these stones are the relics of the last Atlanteans" (Secret Doctrine, vol. 2, p. 341).

Scott-Elliot attributes them to the earlier Lemurians: "They learned to build great cities. These appear to have been of cyclopean architecture, corresponding with the gigantic bodies of the race" (The Story of Atlantis and the Lost Lemuria, p. 101). They were between twelve and fifteen feet tall.Versus TheosophyUp to now we have treated Theosophy only as a source of raw materials used by Lovecraft in his fiction. But occasional references to Theosophy per se imply that he used the cult itself as an image of some kind. We will conclude our consideration of "Lovecraft's use of Theosophy" with a brief survey of four such quotes. In "The Call of Cthulhu", the well-traveled sailor Castro tells what he knows of Cthulhu and the Old Ones. His story "savored of the wildest dreams of myth-maker and theosophist, and disclosed an astonishing degree of cosmic imagination. . . ." In the same story, the narrator describes a file full of data that will eventually disclose the truth about Cthulhu. "The other manuscript papers were all brief notes . . . some of them citations from theosophical books and magazines (notably W. Scott-Elliott's [sic] Atlantis and the Lost Lemuria). . . ." In "Out of the Eons", an eccentric curator is described in these terms: "A smattering of theosophical lore . . . made Reynolds especially alert toward any eonian relic like the unknown mummy."

In all these instances, the implications contain a dim hint of an archaic truth terrible in its reality. It is as if to say that the Theosophists have only a small part of the truth, and that their little knowledge is an extraordinarily dangerous thing. In fact, HPL's narrator says as much in our fourth quote (again, from "The Call of Cthulhu"): "Theosophists have guessed at the awesome grandeur of the cosmic cycle wherein our world and human race form transient incidents. They have hinted at strange survivals in terms which would freeze the blood if not masked by a bland optimism." There is, so to speak, indeed something at the end of the rainbow, only instead of a pot of gold, it is a bottomless pit. In their occultist optimism, Theosophists had postulated the ancient origin of humanity amid alien super-intelligences. So glorious an origin seemed to imply a bright destiny for the race. But Lovecraft's "cosmic futilitarianism" led him to repaint the picture in darker, pessimistic hues. As depicted in At the Mountains of Madness, the genesis of the human race was a breeding accident in the laboratories of the star-headed Old Ones. The resultant vision is one of absurdity. Lovecraft has represented precisely what fundamentalist "creationists" see as being at stake in their quixotic crusade against Darwinism: if man's origin was random, so is his meaning, and so will be his destiny

|

Anexos

Última edição:

Ilmarinen

Usuário

Nessa de pesquisar os análogos na Marvel pintou a inspiração de procurar correspondentes na DC. A pesquisa rendeu um dado interessante: os equivalentes lovecraftianos no DCU são muito menos óbvios do que os da Marvel.

Acho que isso se deve a um fato aplicável também ao Perelandra de C.S.Lewis em contraste ao Legendarium de Tolkien que é mais repleto de imagética lovecraftiana a despeito de sua teologia judaico-cristã "paganizada"; são os deuses "benignos" da Trilogia do Espaço exterior que, inadvertidamente, acabam se apresentando como fractais lovecraftianos cuja mera contemplação é desorientadora pra psiquê humana.Bem nessa linha, os "deuses" apolíneos dos panteões da DC são muito mais "lovecraftianos" do que suas contrapartes marvetes.

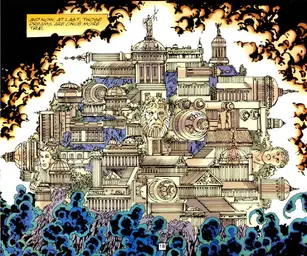

Virtualmente, todas as histórias, numa hora ou outra, demonstram que os deuses são muito mais do que poderia ser sugerido por suas personificações antropomórficas, seus tamanhos variam constantemente, e a própria geometria e gravidade do lugar que habitam já repercute elementos não-euclidianos, bem aos moldes da descrição que Lovecraft fez de R'lyeh no Chamado de Cthulhu.

Vide aí comparação da arquitetura não euclidiana dessa representação de R'lyeh com o Monte Olimpo da DC.

Lovecraft and Mathematics Non Eucliden Geometry

The Weird Physics of H.P. Lovecraft’s "Corpse-City," R’lyeh

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

Quanto aos análogos cthulhianos propriamente ditos, começando pelos exemplos mais evidentes, nós temos:

[URL='http://dc.wikia.com/wiki/Superman_Annual_Vol_1_13']Arion e sua forma Cthulhu assumida durante a luta com Superman

De longe, a mais blatant de todas as homenagens quadrinísticas a Cthulhu foi aqui perpetrada por Kurt Busiek e Carlos Pacheco no clímax de sua saga conjunta na revista do Superman.

Numa história feita pelo mentor intelectual do desenho dos Real Ghostbusters, o J. Michael Straczynski, nós tivemos uma verdadeira aparição convidada de Cthulhu sem ser nomeado

Astro convidado em Brave and the Bold 32

Podemos ver que foi, bem provavelmente, chupinhada dessa picture aí

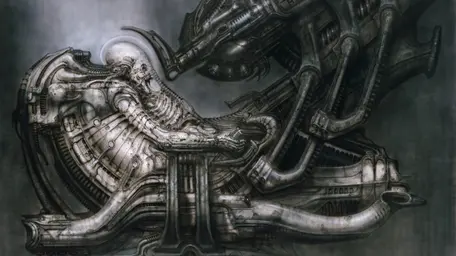

Meio que fechando com as referências cruzadas a Alien ( o corpo das versões de cthulhu acima é bem reminiscente do xenomorfo favorito de todos) está outro análogo de Cthulhu.

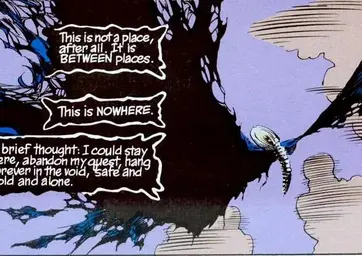

Sandman, Morfeus, usando o Elmo

Andaram observando uma coisa que sempre foi o óbvio ululante: o Sandman com o elmo é idêntico ao Space Jockey de Alien Um agora revelado como sendo um dos Engenheiros em Prometheus, até então todo mundo pensava que o crânio elefantino ou octopóide do Jockey era uma cabeça ossificada mas, o filme mesmo agora homenageou Sandman que já homenageava alien e a referência lovecraftiana ao Cthulhu, revelando que o Jockey também usava um elmo que era parte de seu traje espacial.

Detalhe: o elmo de Morpheus é MESMO o crânio e parte da espinha de um deus que Morfeus foi obrigado a combater, o qual junto com dois outros deuses ( cujos despojos formam os portões de chifres e de marfim do Sonhar) tentou usurpar o Sonhar do Perpétuo. Só agora me parece que Neil Gaiman estava insinuando que o Moldador havia assassinado um análogo de Cthulhu que é, justamente, um "Deus sonhador". Piadinha esperta.

O visual do elmo podia ser tanto uma referência ao Cthulhu quanto ao Deus Elefante do Robert E. Howard, Yag Kosha, na verdade um alienígena capturado por um bruxo que tinha a maior parte de seus poderes canalizados numa jóia parecida com um rubi roubada pelo mago, bem aos moldes do que ocorre com Morfeus no início da revista do Gaiman. E eu juro galera: essas correlações todas só me ocorreram à medida em que escrevo esse post

Asas de escuridão" , "manto de trevas onde podiam ser vistas chamas", hein Gaiman?Desconfio se vc um dia não suspeitou do mesmo que eu...

E, admitamos, o space jockey sempre foi totalmente lovecraftiano/cthulhiano, e o próprio Robert E. Howard era fã de carteirinha do conto do Lovecraft, então, olhando bem Yag Kosha era um Cthulhu bonzinho

Notinha adicional: numa dessas piadinhas internas que os autores fazem uns aos outros, JMS de Babylon 5 e Ghostbusters homenageou Neil Gaiman baseando uma raça de B5 batizada numa sátira do sobrenome "gaiman" dele, os Gaim. O visual deles é feito em cima de Morpheus com o elmo. Sintomaticamente, debaixo dos elmos eles lembram um bocado a cara de... Cthulhu.

Adendo: acredita-se que crânios de elefantes podem ter sido a inspiração pro mito dos ciclopes.Daí quem sabe a conexão: único olho, terceira visão, a pedra mágica que assume coloração vermelha e que foi roubada pelo mago Yara...

Grullug Garkush do Círculo Negro na Legião dos Superheróis, membro da raça dos N'crons

O próprio nome da organização a qual Grullug pertence já é uma referência tangenciando o lovecraftiano já que existe também o Círculo Negro da Era Hiboriana de Robert E. Howard. O da DC é Dark Circle enquanto a versão hiboriana é Black Circle.

Ichthultu

Apareceu como o Cthulhu purgado de impedimentos autorais na série animada da Liga da Justiça.

Lobotomizado pela Clava de N'th metal da Hawkwoman no desenho. Um final meio indigno pra um cthulhu analogue.

Piadinha interna: "In universe" ele pode ter servido de base pro visual da nave da Legião do Mal que, na versão original do desenho, em si mesma é algo reminiscente de Cthulhu também. Pra não falar, é claro, da máscara de Darth Vader.

M'nagallah o Deus Câncer, que, supostamente teria sido o criador da vida na terra, num dos maiores tropos lovecraftianos, o twist na condição de humanos como raça eleita e do "feito à imagem e semelhança de Deus". Ele mesmo baseado no Ubbo Sathla do colega de Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, mais propriamente do que no Cthulhu. Também influencia o desenvolvimento da raça humana via sonhos emitidos como influência sobre cérebros receptivos, teria no DCU sido o inspirador das obras de Poe, Ambrose Bierce e , claro, H.P. Lovecraft

Acho que isso se deve a um fato aplicável também ao Perelandra de C.S.Lewis em contraste ao Legendarium de Tolkien que é mais repleto de imagética lovecraftiana a despeito de sua teologia judaico-cristã "paganizada"; são os deuses "benignos" da Trilogia do Espaço exterior que, inadvertidamente, acabam se apresentando como fractais lovecraftianos cuja mera contemplação é desorientadora pra psiquê humana.Bem nessa linha, os "deuses" apolíneos dos panteões da DC são muito mais "lovecraftianos" do que suas contrapartes marvetes.

Virtualmente, todas as histórias, numa hora ou outra, demonstram que os deuses são muito mais do que poderia ser sugerido por suas personificações antropomórficas, seus tamanhos variam constantemente, e a própria geometria e gravidade do lugar que habitam já repercute elementos não-euclidianos, bem aos moldes da descrição que Lovecraft fez de R'lyeh no Chamado de Cthulhu.

Vide aí comparação da arquitetura não euclidiana dessa representação de R'lyeh com o Monte Olimpo da DC.

Without knowing what futurism is like, Johansen achieved something very close to it when he spoke of the city; for instead of describing any definite structure or building, he dwells only on broad impressions of vast angles and stone surfaces—surfaces too great to belong to any thing right or proper for this earth, and impious with horrible images and hieroglyphs. I mention his talk about angles because it suggests something Wilcox had told me of his awful dreams. He had said that the geometry of the dream-place he saw was abnormal, non-Euclidean, and loathsomely redolent of spheres and dimensions apart from ours. Now an unlettered seaman felt the same thing whilst gazing at the terrible reality.

Lovecraft and Mathematics Non Eucliden Geometry

The Weird Physics of H.P. Lovecraft’s "Corpse-City," R’lyeh

Log into Facebook

Log into Facebook to start sharing and connecting with your friends, family, and people you know.

www.facebook.com

www.facebook.com

Quanto aos análogos cthulhianos propriamente ditos, começando pelos exemplos mais evidentes, nós temos:

[URL='http://dc.wikia.com/wiki/Superman_Annual_Vol_1_13']Arion e sua forma Cthulhu assumida durante a luta com Superman

De longe, a mais blatant de todas as homenagens quadrinísticas a Cthulhu foi aqui perpetrada por Kurt Busiek e Carlos Pacheco no clímax de sua saga conjunta na revista do Superman.

Numa história feita pelo mentor intelectual do desenho dos Real Ghostbusters, o J. Michael Straczynski, nós tivemos uma verdadeira aparição convidada de Cthulhu sem ser nomeado

Astro convidado em Brave and the Bold 32

Podemos ver que foi, bem provavelmente, chupinhada dessa picture aí

Meio que fechando com as referências cruzadas a Alien ( o corpo das versões de cthulhu acima é bem reminiscente do xenomorfo favorito de todos) está outro análogo de Cthulhu.

Sandman, Morfeus, usando o Elmo

Andaram observando uma coisa que sempre foi o óbvio ululante: o Sandman com o elmo é idêntico ao Space Jockey de Alien Um agora revelado como sendo um dos Engenheiros em Prometheus, até então todo mundo pensava que o crânio elefantino ou octopóide do Jockey era uma cabeça ossificada mas, o filme mesmo agora homenageou Sandman que já homenageava alien e a referência lovecraftiana ao Cthulhu, revelando que o Jockey também usava um elmo que era parte de seu traje espacial.

Detalhe: o elmo de Morpheus é MESMO o crânio e parte da espinha de um deus que Morfeus foi obrigado a combater, o qual junto com dois outros deuses ( cujos despojos formam os portões de chifres e de marfim do Sonhar) tentou usurpar o Sonhar do Perpétuo. Só agora me parece que Neil Gaiman estava insinuando que o Moldador havia assassinado um análogo de Cthulhu que é, justamente, um "Deus sonhador". Piadinha esperta.

had this thought too!

I also went into the movie thinking it was going to be sort of Lovecraftian, and then it wasn’t except for these helmets which, as stated above, look like Dream’s helmet. Which, I am pretty sure, he made from Cthulhu’s bones. So.

O visual do elmo podia ser tanto uma referência ao Cthulhu quanto ao Deus Elefante do Robert E. Howard, Yag Kosha, na verdade um alienígena capturado por um bruxo que tinha a maior parte de seus poderes canalizados numa jóia parecida com um rubi roubada pelo mago, bem aos moldes do que ocorre com Morfeus no início da revista do Gaiman. E eu juro galera: essas correlações todas só me ocorreram à medida em que escrevo esse post

Asas de escuridão" , "manto de trevas onde podiam ser vistas chamas", hein Gaiman?Desconfio se vc um dia não suspeitou do mesmo que eu...

E, admitamos, o space jockey sempre foi totalmente lovecraftiano/cthulhiano, e o próprio Robert E. Howard era fã de carteirinha do conto do Lovecraft, então, olhando bem Yag Kosha era um Cthulhu bonzinho

Notinha adicional: numa dessas piadinhas internas que os autores fazem uns aos outros, JMS de Babylon 5 e Ghostbusters homenageou Neil Gaiman baseando uma raça de B5 batizada numa sátira do sobrenome "gaiman" dele, os Gaim. O visual deles é feito em cima de Morpheus com o elmo. Sintomaticamente, debaixo dos elmos eles lembram um bocado a cara de... Cthulhu.

Indeed, the Gaim are an homage to Sandman, having been on the series since

season 1. (Interestingly enough, under the helmets, the Gaim turn out to

look an awful lot like Cthulhu, of all things...

Adendo: acredita-se que crânios de elefantes podem ter sido a inspiração pro mito dos ciclopes.Daí quem sabe a conexão: único olho, terceira visão, a pedra mágica que assume coloração vermelha e que foi roubada pelo mago Yara...

Grullug Garkush do Círculo Negro na Legião dos Superheróis, membro da raça dos N'crons

O próprio nome da organização a qual Grullug pertence já é uma referência tangenciando o lovecraftiano já que existe também o Círculo Negro da Era Hiboriana de Robert E. Howard. O da DC é Dark Circle enquanto a versão hiboriana é Black Circle.

Ichthultu

Apareceu como o Cthulhu purgado de impedimentos autorais na série animada da Liga da Justiça.

Lobotomizado pela Clava de N'th metal da Hawkwoman no desenho. Um final meio indigno pra um cthulhu analogue.

Piadinha interna: "In universe" ele pode ter servido de base pro visual da nave da Legião do Mal que, na versão original do desenho, em si mesma é algo reminiscente de Cthulhu também. Pra não falar, é claro, da máscara de Darth Vader.

M'nagallah o Deus Câncer, que, supostamente teria sido o criador da vida na terra, num dos maiores tropos lovecraftianos, o twist na condição de humanos como raça eleita e do "feito à imagem e semelhança de Deus". Ele mesmo baseado no Ubbo Sathla do colega de Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, mais propriamente do que no Cthulhu. Também influencia o desenvolvimento da raça humana via sonhos emitidos como influência sobre cérebros receptivos, teria no DCU sido o inspirador das obras de Poe, Ambrose Bierce e , claro, H.P. Lovecraft

Anexos

-

SupermanAnnual13-16.webp308,8 KB · Visualizações: 9

SupermanAnnual13-16.webp308,8 KB · Visualizações: 9 -

superman x arion cthulhu.webp56,3 KB · Visualizações: 486

superman x arion cthulhu.webp56,3 KB · Visualizações: 486 -

dream.webp35,5 KB · Visualizações: 478

dream.webp35,5 KB · Visualizações: 478 -

tumblr_m5gbyikmCq1qb6dklo1_500.webp14,4 KB · Visualizações: 518

tumblr_m5gbyikmCq1qb6dklo1_500.webp14,4 KB · Visualizações: 518 -

R'yleh_by_MarcSimonetti.webp35,8 KB · Visualizações: 465

R'yleh_by_MarcSimonetti.webp35,8 KB · Visualizações: 465 -

non euclidian lovecraft mathematics.pdf822,4 KB · Visualizações: 0

Última edição:

Tópicos similares

Clube de Leitura

15º Conto: O horror de Dunwich (H. P. Lovecraft)

- Respostas

- 6

- Visualizações

- 355

- Respostas

- 8

- Visualizações

- 2K

- Respostas

- 4

- Visualizações

- 983

- Respostas

- 27

- Visualizações

- 3K

Clube de Leitura

13º Conto - Kholstomér (Tolstói)

- Respostas

- 12

- Visualizações

- 2K

Compartilhar: