Poxa, o episódio, para quem curte/é entusiasta da história militar antiga/medieval, têm muitos pontos positivos e referências legais. É a primeira vez que vimos o uso "industrial" e mortífero de verdadeiras coortes de arqueiros na linha de frente para enfraquecer e causar o maior dano possível no avanço da vanguarda inimiga. Para quem joga total war deve de ter se extasiado:

Agora no que tange ao seu uso. Ramsey mandou várias saraivadas em suas próprias unidades de cavalaria. Acho que a melhor decisão seria ter mandado um grupo menor de cavalaria atacar Jon e massacrá-lo. Mas como haveria o embate de um grupamento à outro - eu recuaria a cavalaria e faria um ataque combinado de chuva de flechas para matar os cavaleiros e mandaria a cavalaria terminar o serviço nas linhas inimigas que deveriam de tá desorganizadas com as possíveis perdas. Poderia ser mais ou menos o que aconteceu na batalha de Agincourt:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Agincourt

Em vez disso temos o embate frontal de cavalaria (leve e pesada) - um entrechoque que pela primeira vez mostrou o que o Robert Baratheon frisou na 1ª temporada:

They never tell you how they all shit themselves. They don't put that part in the songs... stupid boy. Now the Tarlys bend the knee like everyone else. He could have lingered on the edge of the battle with the smart boys, and today his wife would be making him miserable, his sons would be ingrates, and he'd be waking three times in the night to piss into a bowl. Wine!

Um momento de realismo militar em contraponto à noção romanceada que normalmente vemos nos livros de fantasia - um exército inimigo maligno sendo derrotado pelas forças campeãs da justiça/corretas num grande embate épico, mas não vemos as mortes, as vísceras, o sangue correndo solto, os cavalos agonizando com seus cavaleiros empilhados em pilhas e mais pilhas de corpos - e isso no momento em que Jon ficou perdido em toda essa confusão - o legal foi o contraste do diretor nesta cena:

O nosso herói enfrentado uma situação de grande impossibilidade, numa mistura de coragem, insensatez, mas de grande bravura como se estivesse perdido/descontextualizado. Um Berserk - um herói clássico desafiando esta morte certa. Tanto quê é nesta cena que Jon parece acordar do transe vingativo (diante da morte do irmão) - despertando para que volte a luta:

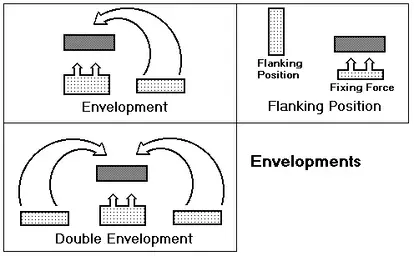

Então vamos para o movimento clássico de pinça/cerco das paredes de escudos Bolton - a forma de avançar; as armas utilizadas e a formação cerrada desta tática muito utilizada na idade média e com reminiscências até hoje:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shield_wall

The formation of a

shield wall (

Scildweall or

Bordweall in Old English,

[1] Skjaldborg in Old Norse) is a

military tactic that was common in many cultures in the Pre-

Early Modern warfare age. There were many slight variations of this tactic among these cultures, but in general, a shield wall was a "wall of

shields" formed by soldiers standing in

formation shoulder to shoulder, holding their shields so that they abut or overlap. Each soldier benefits from the protection of their neighbours' shields as well as their own.

A forma de avanço cerrado e seu sons rítmicos me lembraram um pouco a formação cerrada dos hoplitas gregos e suas falanges:

The

phalanx (

Ancient Greek: φάλαγξ,

Greek: φάλαγγα, phālanga; plural

phalanxes or

phalanges; Ancient and Modern Greek: φάλαγγες, phālanges) was a

rectangular mass military

formation, usually composed entirely of

heavy infantry armed with

spears,

pikes,

sarissas, or similar

weapons. The term is particularly (and originally) used to describe the use of this formation in

Ancient Greek warfare, although the ancient Greek writers used it to also describe any massed infantry formation, regardless of its equipment, as does

Arrian in his

Array against the Alans when he refers to his legions. In Greek texts, the phalanx may be deployed for battle, on the march, even camped, thus describing the mass of infantry or cavalry that would deploy in line during battle. They marched forward as one entity. The word phalanx is derived from the Greek word

phalangos, meaning

finger.

Um exército cercado e sem condições de abrir qualquer brecha nas linhas de defesa é quase certo que será praticamente massacrado, ainda mais com a opção da tática da bigorna e do martelo adotada pelos Bolton - uma reminiscência prática do que é estudado até hoje na batalha de Cannae - em que Hanibal Barca destronou uma força romana superior cercando todos os efetivos:

httpsn://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Cannae

Vs:

e:

Que paralelo estranho:

Gelo e Fogo:

Na série, Bolton cerca os flancos. Os Umber atacam a retaguarda e olegal é que se aproveitam das pilhas de corpos da retaguarda Stark - utilizando este terreno "natural" para impedir qualquer retirada no sufocamento das forças inimigas cercadas, e atacando quem o tentasse - no uso tático do High Ground - terreno alto:

http://www.therightplanet.com/2012/08/on-death-ground/

Já diria Sun Tzu:

“It is a military axiom not to advance uphill against the enemy, nor to oppose him when he comes downhill.”

O que seria um massacre certo - chegamos aos finalmente e Sonsa e Littlefinger quebram a formação de cerco Bolton e o contra ataque se converte na Tática da Martelo e Bigorna em favor dos Starks até então encurralados - realmente Rohan chegou na hora:

Sobre a tática da Hammer and Anvil:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hammer_and_anvil

The hammer and anvil is a relatively simple maneuver. It begins with two

infantry forces of varying strengths engaging in a

frontal assault. While the infantry lines are fixed in the engagement, a

cavalry force maneuvers around the enemy and attacks from behind, sandwiching it into the friendly infantry. Generally, the force attempting the maneuver needs to have a superior amount of cavalry to be successful. This military maneuver was popular in a number of battles throughout the Classical Period. In addition to being used in many of Alexander the Great's battles, this tactic was also used during the Second Punic Wars, specifically the

Battle of Cannae and the

Battle of Zama

No final das contas foi uma vitória Pírrica para os Starks:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pyrrhic_victory

A

Pyrrhic victory is a victory that inflicts such a devastating toll on the victor that it is tantamount to defeat. Someone who wins a Pyrrhic victory has been victorious in some way. However, the heavy toll negates any sense of achievement or profit. Another term for this would be "

hollow victory"

Sobre Dany e os dragões - acho que a inspiração vem das vitórias Bizantinas nos cercos à Constantinopla com o uso do Fogo Grego:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_fire

Greek fire was an

incendiary weapon developed c. 672 and used by the

Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. The Byzantines typically used it in

naval battles to great effect, as it could continue burning while floating on water. It provided a technological advantage and was responsible for many key Byzantine military victories, most notably the salvation of

Constantinople from two

Arab sieges, thus securing the Empire's survival.

vs

-------

Isso me fez ficar empolgado com que venha a acontecer com Stannis no Livro 6. Se as teorias que correm por aí estiverem corretas, Stannis se utilizará de um terreno natural que surgiu por acaso no 5° livro: o lago de gelo onde eles emburacaram na busca por peixes. Neste sentido, em termos militares ele pode fazer igual ao que os Russos fizeram contra os cavaleiros Teutônicos: A batalha do gelo

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_on_the_Ice

The

Battle on the Ice (

Russian: Ледовое побоище,

Ledovoye poboish'ye;

German:

Schlacht auf dem Eise;

Estonian:

Jäälahing;

German:

Schlacht auf dem Peipussee;

Russian: битва на Чудском озере,

bitva na Chudskom ozere) was fought between the

Republic of Novgorod led by prince

Alexander Nevsky and the crusader army led by the

Livonian branch of the

Teutonic Knights on April 5, 1242, at

Lake Peipus. The battle is notable for having been fought largely on the frozen lake, and this gave the battle its name.

O plano: