-

Caro Visitante, por que não gastar alguns segundos e criar uma Conta no Fórum Valinor? Desta forma, além de não ver este aviso novamente, poderá participar de nossa comunidade, inserir suas opiniões e sugestões, fazendo parte deste que é um maiores Fóruns de Discussão do Brasil! Aproveite e cadastre-se já!

Você está usando um navegador desatualizado. Ele poderá não mostrar corretamente este fórum.

Você deve atualizá-lo ou utilizar um navegador alternativo.

Você deve atualizá-lo ou utilizar um navegador alternativo.

O mundo de tolkien existe (existiu)?

- Criador do tópico Beautiful nature

- Data de Criação

Yog-Sothoth

Usuário

Tolkien escreveu a nível high-fantasy, quer dizer, tudo se passa numa espécie de realidade paralela. Tudo aquilo que é fictício existe em nossas mentes e em nossas emoções e definitivamente nos influencia considerávelmente na "vida real", no "plano físico".

Não convém entrar num assunto de natureza mística/ocultista, porém, eu particularmente acredito que tudo o que é inventado e acreditado por muitas pessoas, exerce influência no ser humano sim (Da mesma forma que eu acredito que Edgar Allan Poe é atormentado pelo seu corvo, o corvo que visitou os seus umbrais, até os dias de hoje).

Não convém entrar num assunto de natureza mística/ocultista, porém, eu particularmente acredito que tudo o que é inventado e acreditado por muitas pessoas, exerce influência no ser humano sim (Da mesma forma que eu acredito que Edgar Allan Poe é atormentado pelo seu corvo, o corvo que visitou os seus umbrais, até os dias de hoje).

Elring

Depending on what you said, I might kick your ass!

O Legendarium foi concebido para ser uma mitologia da Inglaterra em um tempo muito remoto e esquecido. Nossa sociedade seria uma continuação das Eras de Arda, a 6ª ou 7ª Era do Sol.

Dentro destes conceitos estabelecidos por Tolkien, Arda existiu. O que não se deve é misturar Fantasia com a realidade em que vivemos... por mais deprimente que seja.

Dentro destes conceitos estabelecidos por Tolkien, Arda existiu. O que não se deve é misturar Fantasia com a realidade em que vivemos... por mais deprimente que seja.

Lola la Gitana

Usuário

Basicamente podemos dizer que sim. Tolkien utilizou elementos que conhecia e os transformou. Claro, a Terra Média não existiu devidamente, mas foi criada a partir de elementos que existem no nosso mundo. Como o Pégaso, ninguém viu um cavalo com asas por aí, mas um cavalo todos conhecem assim como as asas de um pássaro, então esses dois elementos que existem constituem o que conhecemos por Pégaso.

Hobbit Desafinado

Usuário

não existe uma vila tipo um condado com fãs de tolkien morando nela? eu sei que existe uma pousada no estilo condado...

EduAC

Usuário

É complicado falar sobre existir ou não, pq se a terra media existisse mesmo não seria assim tão idealizada, seria a terra media "real" com problemas semelhantes ao que enfrentamos todos os dias, mesmo tendo todos os elementos fantasticos que existem nela, se pudessemos ir pra lá aposto que muitos pediriam a Eru pra voltar pra cá, afinal essa é a nossa realidade e o nosso mundo. Nunca conseguiriamos viver a realidade da terra media, pelo fato que estamos acostumados com essa. A Terra media é tão bonita e legal comparada a Terra real porque no final podemos fechar o livro e sair dela.

Última edição:

Thanatos

Mortinho

É complicado falar sobre existir ou não, pq se a terra media existisse mesmo não seria assim tão idealizada, seria a terra media "real" com problemas semelhantes ao que enfrentamos todos os dias, mesmo tendo todos os elementos fantasticos que existem nela, se pudessemos ir pra lá aposto que muitos pediriam a Eru pra voltar pra cá, afinal essa é a nossa realidade e o nosso mundo. Nunca conseguiriamos viver a realidade da terra media, pelo fato que estamos acostumados com essa. A Terra media é tão bonita e legal comparada a Terra real porque no final podemos fechar o livro e sair dela.

Verdade, uma coisa é idealizarmos a Terra-Média, outra é vivermos nela. Não podemos esquecer que apesar de seus grandes feitos, assim como o nosso mundo real, a Terra-Média também possui um cotidiano que não é algo muito inserido nos livros. E mesmo estes cotidianos variam muito de raça para raça, de povo para povo.

EduAC

Usuário

Cara eu ficou imaginando as vezes se realmente vivessemos em Arda, provavelmente não estariamos na Terra Media. Estariamos nas Sunlands do outro lado do Belegaer, provavelmente vivendo numa antiga possessão Numenoriana, que teria virado um grande imperio ou reino (se compararmos com o Brasil), a guerra do anel seria apenas um rumor ou nunca teriamos ouvido falar. Não conheceriamos os altos-elfos, talvez conhecessemos os elfos verdes que provavelmente nos odiariam por destruir suas florestas. Viveriamos em guerra com os povos indigenas que seria muito estranhos a nós. Teriamos provavelmente um mayar vivendo na grandes florestas que teriamos ( vide floresta amazonica) provavelmente uma serva de Yvanna e ela odiaria a nós por causa do fato de destruirmos sua floresta. E por fim seriamos uma mistura de Numenoriano negro ou Gondoriano com Haradrim. Vejam o meu caso Holandes misturado com Português, Indio e Africano.

Foi mal a viagem ai, pelos menos essa seria a visão da Arda "real" pra mim.

Foi mal a viagem ai, pelos menos essa seria a visão da Arda "real" pra mim.

Excluído043

Excluído a pedido

Não, nunca existiu, e antes ele tivesse corrido o risco de ser acusado de "brincar de Deus", pois assim teria evitado o mal maior de ser considerado o "profeta tardio" do Cristianismo por alguns lunáticos mundo afora. Pois é, Tolkien terminou muito parecido com seu personagem Celebrimbor. E além do mais, um mundo imaginário, sem conexão alguma com o nosso, abriria um imenso campo para novas e fascinantes sagas que seriam escritas por seus admiradores. Mas ele preferiu colocar tudo aquilo como ocorrido seis mil anos antes da história conhecida da humanidade (corrijam-me, se eu estiver errado), retirando, pelo menos para mim, boa parte do fascínio que sua obra tinha e o substituindo por melancolia. Avaliação de crítico, afinal era a sua ( de Tolkien) obra e ele podia declarar o que quisesse sobre ela.

Última edição:

Excluído045

Banned

Profeta tardio do cristianismo é exagero, agora que sua obra é essencialmente influenciada pelo cristianismo católico-romano, tanto em cosmologia como em teologia, isso é inegável.

Excluído043

Excluído a pedido

Eu afirmei que há dementes que consideram Tolkien um "profeta tardio" do Cristianismo, eu mesmo conheço um. Tolkien jamais diria tal coisa.

Última edição:

EduAC

Usuário

Cara o fato dele ter imaginado o mundo dele 6 mil antes da historia conhecida da humanidade, não matou a possibilidade de outros virem e continuarem seu trabalho. Ninguem quis explicar o que ocorreu no final da 4 quarta era que fez desaparecer o mundo tolkieano,ninguem explicou o que teria nas darklands e sunlands. Como seria a vida dos elfos que ainda existiriam hoje, o tolkien deixa um monte de brechas, a maioria que não se aproveita delas, preferem fica voltando a formulas batidas como primeira era e a saga do senhor dos aneis. É tudo uma questão de ter criatividade.Não, nunca existiu, e antes ele tivesse corrido o risco de ser acusado de "brincar de Deus", pois assim teria evitado o mal maior de ser considerado o "profeta tardio" do Cristianismo por alguns lunáticos mundo afora. Pois é, Tolkien terminou muito parecido com seu personagem Celebrimbor. E além do mais, um mundo imaginário, sem conexão alguma com o nosso, abriria um imenso campo para novas e fascinantes sagas que seriam escritas por seus admiradores. Mas ele preferiu colocar tudo aquilo como ocorrido seis mil anos antes da história conhecida da humanidade (corrijam-me, se eu estiver errado), retirando, pelo menos para mim, boa parte do fascínio que sua obra tinha e o substituindo por melancolia. Avaliação de crítico, afinal era a sua ( de Tolkien) obra e ele podia declarar o que quisesse sobre ela.

Eów Dernhelm

Amigável mesmo sendo um...

Profeta tardio do cristianismo é exagero, agora que sua obra é essencialmente influenciada pelo cristianismo católico-romano, tanto em cosmologia como em teologia, isso é inegável.

Não só a obra dele, como se for analisar a obra de Lewis tambem possui grande influência fo Cristianismo. Com relação a ele ser considerado um "profeta" eu não sabia, e não consigo compreender como alguém pôde chegar a uma conclusão com esta. Enfim nunca existiu, mas a maneira pela qual ele colocou a sua historia como se a mesma realmente estivesse realmente inserida dentro da historia da humanidade isso já demonstra pelo menos aos meus olhos uma genialidade incrível!

Excluído043

Excluído a pedido

Pois eu preferiria que aquele mundo continuasse "existindo" em todas as possibilidades, adoraria ler, ou até escrever, por exemplo, sobre o "apocalipse élfico", quando o Belo Povo finalmente teria de encarar o seu fim e a lógica corrupção de boa parte deles (afinal eles não sabem qual será o destino de seus espíritos, após o fim de Arda, pelo que eu compreendi lendo o "Silmarillion", somente homens, maiar e valar têm espíritos verdadeiramente imortais). E poderíamos citar várias outras possibilidades, como novos reinos dunadânicos, nos continentes que surgiram após a destruição de Númenor, dentre diversas outras.

Última edição:

Snaga

Usuário não-confiável!!!

Bom, eu não li o tópico inteiro, mas vi muita gente tirando sarro da cara da menina.

Interessante é que todo mundo aqui é fã de fantasia, todo mundo adora ler a fala mais marcante d'As Crônicas de Nárnia: "O que é que andam ensinando para as crianças na escola hoje em dia?" Todo mundo adoro aqueles filmes cuja a mensagem final é: continuem acreditando no impossível, na fantasia!

Mas basta chegar um inocente e todos o crucificam, se acham os donos da razão e tudo o mais. Como se a "razão" fosse mesmo tudo o que importa.

Não digo que as história de Tolkien tenham realmente existido num passado remoto de nossa Terra/Arda. Mas como disse o Vëon lá no início: "existe em nossos corações" e isso é mais que suficiente para dizer que é real.

Deixe as pessoas acreditarem no que quiserem, desde que não firam ninguém, que mal há nisso? Quem dera o mundo fosse feito apenas de inocentes e sonhadores!!!

E, venhamos e convenhamos, TODOS aqui (e nisso eu realmente acredito), todos já se questionaram quanto a isso, seja num momento introspectivo ou num delírio alcoólico, não importa, em pelo menos um instante da sua vida, vocês já se questionaram sobre a real existência do mito tolkieniano. Eu mesmo, quando li SdA pela primeira vez, não vi outra forma de se criar tudo aquilo, se não tivesse realmente sido traduzido do Livro Vermelho.

Interessante é que todo mundo aqui é fã de fantasia, todo mundo adora ler a fala mais marcante d'As Crônicas de Nárnia: "O que é que andam ensinando para as crianças na escola hoje em dia?" Todo mundo adoro aqueles filmes cuja a mensagem final é: continuem acreditando no impossível, na fantasia!

Mas basta chegar um inocente e todos o crucificam, se acham os donos da razão e tudo o mais. Como se a "razão" fosse mesmo tudo o que importa.

Não digo que as história de Tolkien tenham realmente existido num passado remoto de nossa Terra/Arda. Mas como disse o Vëon lá no início: "existe em nossos corações" e isso é mais que suficiente para dizer que é real.

Deixe as pessoas acreditarem no que quiserem, desde que não firam ninguém, que mal há nisso? Quem dera o mundo fosse feito apenas de inocentes e sonhadores!!!

E, venhamos e convenhamos, TODOS aqui (e nisso eu realmente acredito), todos já se questionaram quanto a isso, seja num momento introspectivo ou num delírio alcoólico, não importa, em pelo menos um instante da sua vida, vocês já se questionaram sobre a real existência do mito tolkieniano. Eu mesmo, quando li SdA pela primeira vez, não vi outra forma de se criar tudo aquilo, se não tivesse realmente sido traduzido do Livro Vermelho.

Excluído045

Banned

O problema não é esse, Snaga, mas o fato do fantasismo. Fantasia é muito bom, todos gostamos, mas fantasismo é doença, é algo que te impede de viver, ou pelo menos, de viver bem, viver feliz. Sei disso porque já vivi algo parecido com isso. Toda a conversa em torno do quanto é bom sermos sonhadores é muito bonita e verdadeira até certo ponto, até o ponto em que nossa imaginação começa a falsear realidade. Aí tudo se torna falso.

Snaga

Usuário não-confiável!!!

O problema não é esse, Snaga, mas o fato do fantasismo. Fantasia é muito bom, todos gostamos, mas fantasismo é doença, é algo que te impede de viver, ou pelo menos, de viver bem, viver feliz. Sei disso porque já vivi algo parecido com isso. Toda a conversa em torno do quanto é bom sermos sonhadores é muito bonita e verdadeira até certo ponto, até o ponto em que nossa imaginação começa a falsear realidade. Aí tudo se torna falso.

Para tudo isso existem limites pessoais, Paganus. Todo mundo já passou por isso. Alguns "amadureceram" mais cedo, outros mais tarde, mas hora ou outra, a realidade cai como uma bigorna na cabeça. E por mais que eu, você e todos aqui já tenhamos sido fantasistas em algum período da vida, nem que tenha sido apenas na mais tenra infância, hoje eu sei que todo mundo olha para trás e morre de saudade dos tempos e inocência. É um sentimento praticamente universal. No entanto o amadurecimento é um caminho sem volta.

Então não vejo mal algum em deixar as pessoas sonharem à vontade. Quando o sonho acabar, a única coisa que vai lhes sobrar é a realidade, então...

E outra, alguém sabe a idade dessa menina? No perfil dela nem diz nada.

Ilmarinen

Usuário

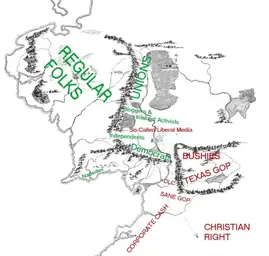

A intenção da obra de Tolkien, de certo modo, é mesmo a de nos fazer pensar ou repensar nossa realidade em cima da idéia de "nostalgia do que nunca foi" e, assim como o Avatar do Cameron ( que perdeu o Oscar por causa de esfregar na cara dos americanos a analogia deliberada com o Iraque e o Vietnã além do massacre dos indios dos EUA), nos fazer refletir sobre o Passado, Presente e Futuro do nosso Mundo Primário de um modo lúdico e transfigurado pelo "Poder do Mito".

O tópico aí tratou disso antes também.Nessa mensagem postada lá ficam sugeridas formas e detalhes do Legendarium segundo os quais Tolkien nos faz pensar a respeito de História da Inglaterra, Catolicismo x Protestantismo, Imperialismo e Colonialismo x coexistência globalizada, racismo e democracia de maneiras sutis e transfiguradas assim como obras como A Divina Comédia, O Paraíso Perdido e o mencionado The Faerie Queene ( até hoje não traduzido pro português por motivos religiosos e políticos e comentado no post linkado acima) também faziam.

O Tolkien realmente acreditava que a Terra já tinha tido mesmo um passado "edênico" embora não exatamente do modo descrito na Bíblia e nem, tampouco, do modo como ele próprio imaginou no seu Legendarium.

Tem essa passagem da biografia dele, cuja tradução em português precisa imediatamente ser reeditada, onde o Humphrey Carpenter disse que o próprio Tolkien acreditava que seu Mito ( há inclusive a anedota de que Tolkien pronunciava mitologia como my-tologia, my-thology) continha vislumbres de uma verdade transcendental que só pode ser parcialmente apreendida no nosso Mundo Primário dentro dos limites do "Tempo sob o Sol".

Fantasia também é realidade. Pro melhor e pro pior!!!

<object width="518" height="419"><param name="movie" value="http://www.mrctv.org/public/eyeblast.swf?v=GdaGaG4zVr" /><param name="allowFullScreen" value="true" /><embed type="application/x-shockwave-flash" src="http://www.mrctv.org/public/eyeblast.swf?v=GdaGaG4zVr" allowfullscreen="true" width="518" height="419" /></object>

Nota: o próprio Avatar também provocou o chamado efeito "blue", o de deprimir muita gente que sentiu a "nostalgia" ou desejo inalcançável pela realidade "paradisíaca" de Pandora.... Similar aos sentimentos expressos no post inaugural do tópico.

Vide aí essa imagem satirista dos innuendos políticos do SdA aplicados à contemporaneidade. "Aplicabilidade" é isso aí gente...

O tópico aí tratou disso antes também.Nessa mensagem postada lá ficam sugeridas formas e detalhes do Legendarium segundo os quais Tolkien nos faz pensar a respeito de História da Inglaterra, Catolicismo x Protestantismo, Imperialismo e Colonialismo x coexistência globalizada, racismo e democracia de maneiras sutis e transfiguradas assim como obras como A Divina Comédia, O Paraíso Perdido e o mencionado The Faerie Queene ( até hoje não traduzido pro português por motivos religiosos e políticos e comentado no post linkado acima) também faziam.

O Tolkien realmente acreditava que a Terra já tinha tido mesmo um passado "edênico" embora não exatamente do modo descrito na Bíblia e nem, tampouco, do modo como ele próprio imaginou no seu Legendarium.

Tem essa passagem da biografia dele, cuja tradução em português precisa imediatamente ser reeditada, onde o Humphrey Carpenter disse que o próprio Tolkien acreditava que seu Mito ( há inclusive a anedota de que Tolkien pronunciava mitologia como my-tologia, my-thology) continha vislumbres de uma verdade transcendental que só pode ser parcialmente apreendida no nosso Mundo Primário dentro dos limites do "Tempo sob o Sol".

When he wrote The Silmarillion Tolkien believed that in one sense he was writing the truth. He did not suppose that precisely such peoples as he described, 'elves', 'dwarves', and malevolent 'orcs', had walked the earth and done the deeds that he recorded. But he did feel, or hope, that his stories were in some sense an embodiment of a profound truth.Time and again he expressed his distaste for that form of literature. 'I dislike allegory wherever I smell it,' he once said, and similar phrases echo through his letters to readers of his books. So in what sense did he suppose The Silmarillion to be 'true'?

Something of the answer can be found in his essay On Fairy-Stories

and in his story Leaf by Niggle, both of which suggest that a man may be given by God the gift of recording 'a sudden glimpse of the

underlying reality or truth'. Certainly while writing The Silmarillion

Tolkien believed that he was doing more than inventing a story. He wrote of the tales that make up the book: They arose in my mind as "given" things, and as they came, separately, so too the links grew. An absorbing, though continually interrupted labour (especially, even apart from the necessities of life, since the mind would wing to the other pole and spread itself on the linguistics): yet always I had the sense of recording what was already "there", somewhere: not of "inventing".'

He had shown the original Earendel lines to G.B. Smith, who had said that he liked them but asked what they were really about. Tolkien had replied: 'I don't know. I'll try to find out.' Not try to invent: try to find out. He did not see himself as an inventor of story but as a discoverer of legend. And this was really due to his private languages.

It is impossible in a few sentences to give an adequate account of how Tolkien used his elvish languages to make names for the characters andplaces in his stories. But briefly, what happened was this. When working to plan he would form all these names with great care, first deciding on the meaning, and then developing its form first in one language and subsequently in the other; the form finally used was most frequently that in Sindarin. However, in practice he was often more arbitrary. It seems strange in view of his deep love of careful invention, yet often in the heat of writing he would construct a name that sounded appropriate to the character without paying more than cursory attention to itslinguistic origins. Later he dismissed many of the names made in this way as 'meaningless', and he subjected others to a severe philological scrutiny in an attempt to discover how they could have reached their strange and apparently inexplicable form. This, too, is an aspect of his imagination that must be grasped by anyone trying to understand how he worked. As the years went by he came more and more to regard his own invented languages and stories as 'real' languages and historical chronicles that needed to be elucidated. In other words, when in this mood he did not say of an apparent contradiction in the narrative or an unsatisfactory name: 'This is not as I wish it to be; I must change it.' Instead he would approach the problem with the attitude: 'What does his mean? I must find out.'

This was not because he had lost his wits or his sense of proportion. In part it was an intellectual game of Patience1 (he was very fond of Patience cards), and in part it grew from his belief in the ultimate truth of his mythology. Yet at other times he would consider making drastic changes in some radical aspect of the whole structure of the story, just as any other author would do. These were of course contradictory attitudes; but here as in so many areas of his personality Tolkien was a man of antitheses.

Fantasia também é realidade. Pro melhor e pro pior!!!

<object width="518" height="419"><param name="movie" value="http://www.mrctv.org/public/eyeblast.swf?v=GdaGaG4zVr" /><param name="allowFullScreen" value="true" /><embed type="application/x-shockwave-flash" src="http://www.mrctv.org/public/eyeblast.swf?v=GdaGaG4zVr" allowfullscreen="true" width="518" height="419" /></object>

Nota: o próprio Avatar também provocou o chamado efeito "blue", o de deprimir muita gente que sentiu a "nostalgia" ou desejo inalcançável pela realidade "paradisíaca" de Pandora.... Similar aos sentimentos expressos no post inaugural do tópico.

Vide aí essa imagem satirista dos innuendos políticos do SdA aplicados à contemporaneidade. "Aplicabilidade" é isso aí gente...

Anexos

Última edição:

EduAC

Usuário

Muito interessante, o estranho é que não tem nada falando sobre os romanos. Eles em muitas ocasiões defenderam os celtas contras as invasões barbaras e foram historicamente os primeiros a propagarem o cristianismo na europa e na inglaterra e nos meados do seculo 5 depois de cristo partem da inglaterra, mas não indo pro oeste e sim pro sul.

O engraçado é que tolkien não fala em nenhum imperio ou reino do sul, a não ser gondor, mas isso já é na terceria era.

O engraçado é que tolkien não fala em nenhum imperio ou reino do sul, a não ser gondor, mas isso já é na terceria era.

Morfindel Werwulf Rúnarmo

Geofísico entende de terremoto

que perdeu o Oscar por causa de esfregar na cara dos americanos a analogia deliberada com o Iraque e o Vietnã além do massacre dos indios dos EUA

Eu também reparei nisso, mas caíram em cima de mim quando eu disse isso. O filme é muito bom, mas aqui não é o lugar.

Tópicos similares

- Respostas

- 1

- Visualizações

- 523

- Respostas

- 0

- Visualizações

- 662

- Respostas

- 1

- Visualizações

- 1K

- Respostas

- 3

- Visualizações

- 167

Compartilhar: